Commentary

In crucial times, we would be fortunate indeed if the leaders of the free world were as courageous, as principled, and as great communicators as Winston Churchill, Ronald Reagan, and Margaret Thatcher.

But such leaders are, unfortunately, rare.

Ordinary leaders have in the past resorted to appeasement, that is, being too ready to make significant and unnecessary concessions to the enemy.

We are living in one of those times when a general war with powers hostile to our way of life seems to be looming but is of course not inevitable. That our potential enemies are coming together is a warning sign.

Our predecessors had the Berlin-Rome-Tokyo Axis, made worse by the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Nazi Germany and Communist Russia with its cynical secret clauses dividing Eastern Europe between them.

Today, we are witnessing a strengthening hostile alliance—the Beijing-Moscow-Tehran Axis.

We are already seeing the appeasement of this Axis. That is bad enough. The question has to be asked, is this worse than the appeasement we saw before and during the Second World War?

To what extent are so many of the American elites in the ruling class morally compromised in their relations with Beijing?

We can learn much about appeasement, at least in its honourable form, from the Second World War.

In the thirties, when the United States was isolationist, the most prominent appeasers were the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, and a prominent Conservative minister, Lord Halifax.

In the 1938 Munich Agreement, Chamberlain agreed to surrender to Hitler what was not his, the mainly German-populated Czech Sudetenland, all to avoid war.

Chamberlain agreed to this on the understanding that Hitler, as he claimed, had no other territorial ambitions in Europe. A glance at Hitler’s autobiography, Mein Kampf , should have persuaded him that this was an obvious lie. Nevertheless, Chamberlain returned to London in triumph with an agreement, one which he said delivered “Peace in Our Time.”

While the appeasers are universally condemned today, we too easily forget that, although misguided, they were honourable and moreover, enjoyed strong popular support. Like most of the population at the time, they were mesmerised by the horror of the First World War that had destroyed too much of a generation of the best, left either dead or mentally and physically damaged. They feared that this tragedy would be repeated.

Unsurprisingly, when Chamberlain had earlier announced his mission to Munich to a crowded House of Commons, he was greeted by a rare standing ovation, even from the diplomatic galleries. Only Churchill and his closest colleagues remained seated.

Churchill was right to be wary. Not content with just the Sudetenland, Hitler soon took all of Czechoslovakia and then moved on to Poland. Ignoring Chamberlain’s ultimatum to withdraw, Britain immediately declared war on Nazi Germany in 1939, joined in different ways by her Commonwealth Dominions, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa.

The war did not initially go well for Britain and Chamberlain was forced to resign. The establishment would have preferred Halifax as his successor but he was reluctant. So King George VI called on Churchill to form a government, which became a grand coalition which the Labor Party and the smaller parties joined.

These were dark days. When Churchill announced the formation of his government to the Commons, he famously said: “I would say to the House…(that) I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.”

With France falling to the Nazis (the National Socialist German Workers’ Party), the substantial British Expeditionary Force attempting to return from Dunkirk, the United States neutral, Russia in alliance with Hitler, and most of Europe occupied, Britain and her Empire were alone.

Fearing the situation hopeless, but against Churchill’s opposition, Chamberlain and especially Halifax argued in the five member War Cabinet that Britain’s only recourse after Dunkirk was to seek terms from Hitler.

The War Cabinet was to debate this question over what the Hungarian-born American historian John Lucacs argues were the five most crucial days of the 20th century—May 24 to May 28, 1940. The story is set out superbly in his short but magisterial book “Five Days in London, May 1940.”

Churchill knew that agreeing to terms would require an effective British surrender, no doubt involving the neutralization of the armed forces including the Royal Navy (then the most powerful navy in the world), stopping the armaments industry, handing over bases and colonies across the world, as well as at least sharing political power in Britain with the reviled local fascists.

Hitler would have then clearly won the war, with most of Europe occupied and much of the British and French Empires subjugated by the Nazis and their Communist allies for years—even a generation.

When it was suggested that Britain appeal to President Roosevelt to intervene, telegrams were tabled from the Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies and the South African Prime Minister General Smuts to the president notifying him that, come what may, those distant countries intended to fight on, even if they were alone. From these messages, Churchill argued that the best way for the British to command respect from the American people was by making a bold stand against Hitler.

With the support of the two Labor members of the War Cabinet, Clement Atlee and Arthur Greenwood, and thus a narrow majority, Churchill went to the full Cabinet for their support in not seeking terms from Hitler, arguing dramatically that “if this long island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each one of us lies choking in his own blood upon the ground.”

Approval for this rallying call was unanimous with not even the faintest flicker of dissent. Churchill, a great leader, had prevailed over appeasement even when the future of resistance seemed bleak, if not hopeless. There would be no more appeasement in Europe of the Nazis. And Britain was to fight on, and in all theatres across the world joined by the United States after Pearl Harbour and by Russia when Hitler treacherously turned on her.

Having overcome moves to appease Hitler at the fall of France, the British were still to experience grandiose appeasement in another theatre.

This was on May 15, 1942, when Lieutenant-General Arthur Ernest Percival, acting against Churchill’s specific orders, surrendered the great fortress of Singapore to the Imperial Japanese in the naïve belief that the local Chinese would be treated properly.

In what Churchill rightly described as the “worst disaster” in British military history, about 80,000 British, Indian, and Australian troops in Singapore became prisoners of war, joining the 50,000 already taken prisoner on the Malayan Peninsular Campaign—brutally mistreated, starved, over-worked, tortured and with many killed.

Rather than so unwisely surrendering against orders, Percival would have been advised to counter-attack what subsequent research has revealed as a significantly smaller Japanese force at the end of its supply line and with their artillery having only a few hours of ammunition left.

Britain was also to fight on in Burma and India, and on the seas.

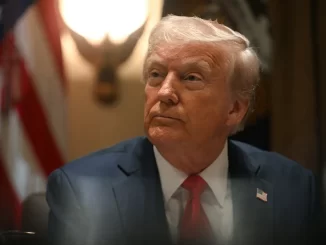

The Second World War teaches us much about appeasement, and how great leadership can fight it. We tend to think that is all in the past. But until the advent of President Donald Trump, much of the reaction of American administrations in recent years towards the aggressive policies, political or economic, adopted by Beijing, Moscow, and Tehran has lacked the strength one would expect from the dominant Western power. It is not unfair to say that the theme, especially that of the Obama-Biden administration, was constantly one of appeasement.

Thus, President Barack Obama was overheard on a live microphone telling the Russian President that he would have to await his re-election to have more “flexibility” on global missile defense, no doubt to come closer to the Russian position.

Then, the Obama-Biden administration was soft on Beijing, both with her increasing aggression in the South China Sea, her human rights violations including the trade in human organs from the Falun Gong while accepting her taking of American intellectual property and her flouting of her WTO obligations.

Then, there was not only the extraordinary and generous surrender to Iran’s nuclear ambitions through the avoidance of constitutional requirements for the approval of a treaty but also strong reports of the derailing of a U.S. law enforcement campaign targeting drug trafficking into the United States by the Iranian-backed terrorist group Hezbollah.

The question which must now be faced is whether America is facing worse than the appeasement that Churchill fought against? So many in the American establishment—industrial, political, academic, cultural, media, and sporting—are dazzled and swayed by the wealth that the CCP offers, notwithstanding the human rights outrages involved from slave labour to organ harvesting.

This is going further than the Second World War appeasement so condemned by history.

David Flint, a former chairman of the Australian Press Council, the Australian Broadcasting Authority, and the World Association of Press Councils is an emeritus professor of law.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.

Be the first to comment