Tom Brokaw’s inspiring book “The Greatest Generation,” about those who came of age during the Great Depression and World War II, revealed an American generation who gave so much and asked for so little. They lived in extraordinary, challenging times but managed to build a better world with the shared values of duty, honor, courage, service, and love of family and country. Above all, they accepted responsibility for their choices.

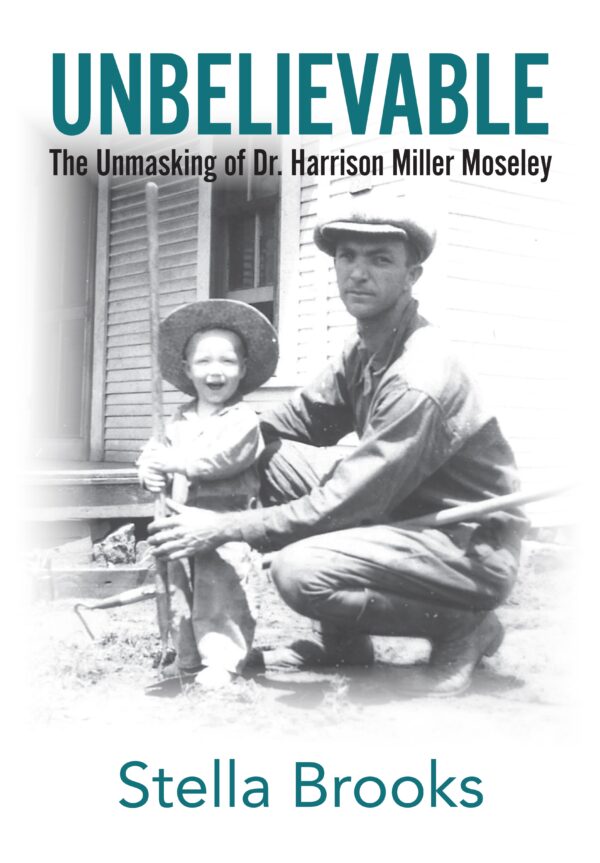

Although “Unbelievable: The Unmasking of Dr. Harrison Miller Moseley” tells its story through the eyes of one man, like Brokaw’s book, it reveals an inspiring generation that is sadly soon to be completely gone from this earth.

When Stella Brooks, who wrote this fascinating biography, was looking to obtain a historical marker for two high school stadiums in Fort Worth, Texas, she discovered information about Dr. Harrison Miller Moseley, who happened to live near her. After several interviews, Brooks was surprised to learn that Moseley’s past had always been a closed book to his family, friends, and acquaintances.

Brooks decided that Moseley’s life story needed to be told, and she devoted two years of her own life to do the telling. And what an interesting tale Moseley had to share. The book demonstrates triumph in the face of adversity and that the perpetual victim mindset so often seen today was absent in the past.

The Young Harrison Miller Moseley

Moseley was born on the plains of Texas in 1921. At a very young age, he lost his father, and although his mother tried to continue business as usual, she couldn’t. All of her children had to help out. Moseley’s younger brother Cecil, 5 years old at the time, picked cotton.

One day, a cotton buyer asked Cecil to show him his hands, which were close to bleeding due to the work. Shortly after, Moseley’s mother, because of the financial pressures of the Depression, put all three of her children in the Masonic Home and School of Texas. She hoped her sacrifice would give her children a better life.

Orphanages have a dreary reputation in literature, but not this one. The Masons took pride in taking excellent care of widows and orphans, and they referred to all the orphans as “their Jewels” and acted accordingly.

Tom Brady, now 96, and a fellow resident with Moseley at the Masonic Home and School, said in a brief phone interview: “I have so many happy memories of my time in the home, it would be hard for me to choose just one. I lost my father, like Moseley, and I was saved from devastation.”

At the home, the boys and girls lived in separate dormitories. Everything was well organized, and the children had assigned tasks. The emphasis was on good habits and sound character. Religious faith was a requirement. Each Sunday, the children went to the school auditorium for Sunday school, and sermons were delivered by the religious heads of varied churches, which gave them an opportunity to hear from their own denominations.

Standing out among Moseley’s adventures at the Masonic Home was his time on the football team. Although the team was regularly outweighed by their opponents by 30 to 50 pounds, the coach, Rusty Russell, used ingenuity in his duties. To complement the team’s small size, Coach Russell cooked up the most imaginative plays, and the team reached football glory.

Russell himself had an interesting story. The World War I vet had been blinded during his service, but he promised God that if his eyesight were to be restored, he would make a difference in a child’s life. His vision was restored in one eye and he kept his promise.

Despite his amazing triumph as part of this team, Moseley would become part of still a greater group.

College and War

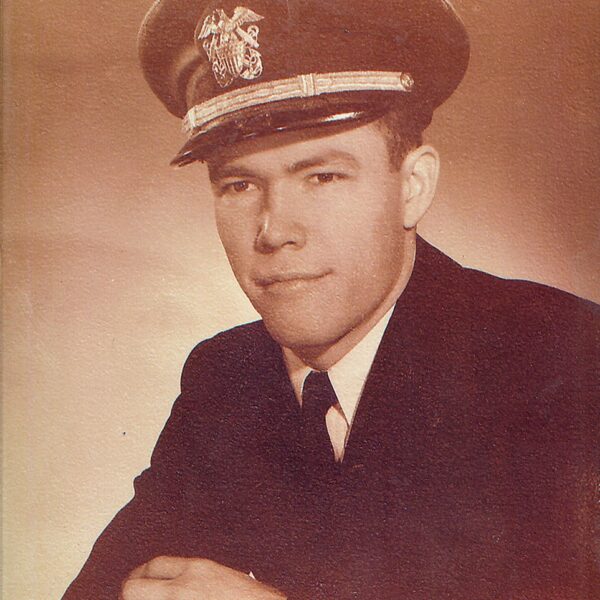

Moseley was the valedictorian of the Masonic Home’s class of 1938. He then went to Texas Christian University on a full academic scholarship and eventually became a physics and chemistry major, graduating at the top of his class. He pursued graduate studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

In 1939, less than four months after Miller graduated from the Masonic Home, Nazi Germany invaded Poland. That year, Albert Einstein successfully convinced President Roosevelt that the United States might be in grave danger if Hitler built the most powerful bomb in the world first. The race to see which nation could produce the first atomic bomb thus began.

Nathan Rosen of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who had been Albert Einstein’s collaborator and friend, was called upon to help. Rosen accepted and brought along his brightest student, Moseley. Moseley then found himself working with the upper echelon of the Manhattan Project. He was assigned a job to work directly under Ross Gunn, the technical adviser of the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory and a member of the federal government’s S-1 Uranium Committee.

It wasn’t until Moseley heard the news reports of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that he learned his group’s research had been a pivotal part of something that had changed the course of the war and world history forever. He downplayed his involvement, saying, “I was just doing my job.”

Life After the War

After the war, Moseley finished his doctorate and returned to Fort Worth, where he landed a job teaching at Texas Christian University and remained there until he retired. “Most of the students sitting in the class with this quiet professor had no idea that he had been an A-list player working with the most-read-about men in history on the most important mission in the world,” Brooks told me in a short interview.

During his time as a professor, Moseley met his wife. She was a widow with three daughters. “He went from the bachelor living in a small apartment over a garage to a large home with four females, a cat, and a dog.” Brooks said.

Moseley had a loving marriage and brought stability to his stepchildren’s lives, as the death of their dad had left them in limbo. He was kind and loving, with a mild manner and a positive attitude. Moseley died in 2014.

Brooks’s enthralling book gives readers a front-row seat to one of the most significant scientific achievements in modern history. Her descriptions are vivid, and her skillful use of language helps readers form detailed mental pictures. Her book has the potential to become a wholesome family film.

Brooks refers to Moseley’s life as unbelievable and inspiring. The readers of her amazing book will certainly agree.

‘Unbelievable: The Unmasking of Dr. Harrison Miller Moseley’

Stella Brooks

June 16, 2020

418 pages, paperback

Linda Wiegenfeld is a retired teacher. She can be reached for comments or suggestions at lwiegenfeld@aol.com

Be the first to comment