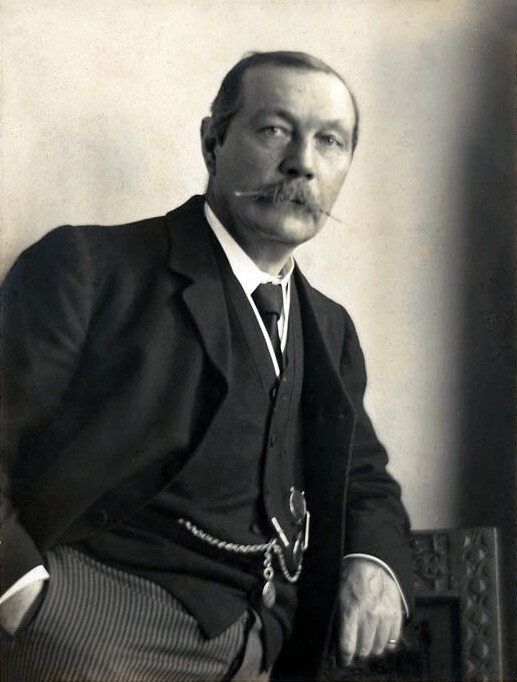

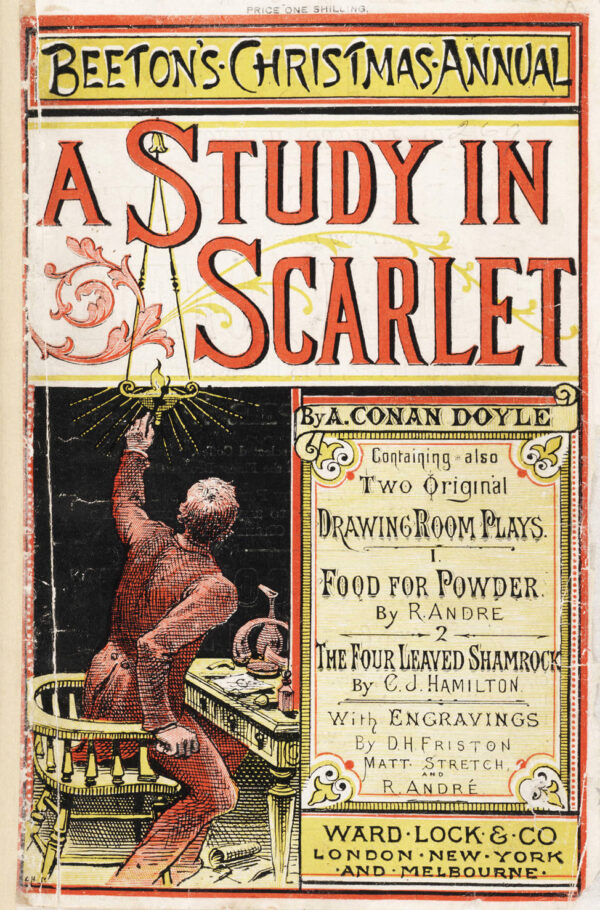

In 1886, a struggling 27-year-old physician named Arthur Conan Doyle made a fateful decision that was intended simply to pay the bills, but that would end up enriching the world. He published a novella featuring an eccentric consulting detective by the name of Sherlock Holmes. With “A Study in Scarlet” appearing in Beeton’s Christmas Annual in 1887, the stage was set for what would prove one of the greatest archetypical creations in the history of literature.

And yet, it was a creation Doyle would destroy, only to realize later that he had started something too powerful for him to end. And one of the initial white flags that Doyle was forced to wave to appease a disapproving public was a trifle in the form of a charming exchange between Holmes and his friend and colleague, Dr. Watson, titled “The Field Bazaar,” published in 1896, 125 years ago this year.

As Mr. Holmes remarked, “there is nothing so important as trifles,” and if it is anything, “The Field Bazaar” is a trifle. The towering mystery of Sherlock Holmes, however, is very much alive in the story’s tiny mystery, as it furthers the saga-shifting concept of apocryphal writings—a suspicion that has egged scholars on and enticed the intellects of readers for over a century, and shall, God willing, for centuries to come.

The Bizarre Origin of ‘The Field Bazaar’

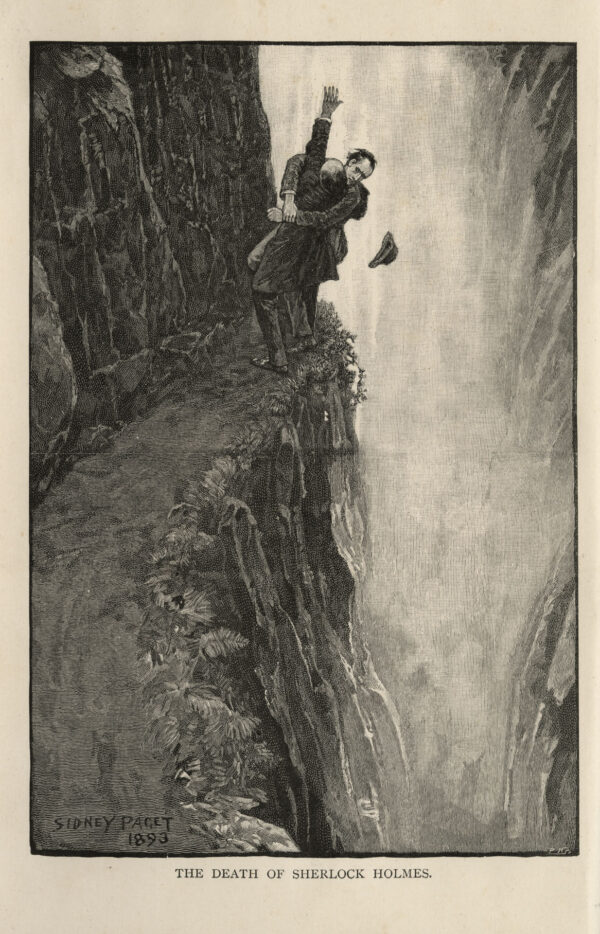

While writing these stories proved successful in covering Doyle’s costs of living, Sherlock Holmes himself came with a price—time and energy. “He takes my mind from better things,” Doyle wrote before releasing “The Final Problem” in 1893, where he finally disposed of his problem and dispatched Sherlock Holmes for good and all, plunging him to his death beneath Switzerland’s Reichenbach Falls in a struggle with his archnemesis, Professor James Moriarty. “Killed Holmes,” Doyle wrote tersely in his diary, and his readership was shocked and dismayed, wore mourning bands in public, and shed tears in private over the impossible pages of The Strand.

Soon the widespread anguish over Holmes’s demise gave way to widespread anger. The rebellion of readers was rumored. In the words of Doyle:

“I was amazed at the concern expressed by the public. They say a man is never properly appreciated until he is dead, and the general protest against my summary execution of Holmes taught me how many and how numerous were his friends. ‘You Brute!’ was the beginning of a letter of remonstrance which one lady sent me, and I expect she spoke for others beside herself … I fear I was utterly callous myself, and only glad to have a chance of opening out into new fields of imagination.”

As Doyle considered the pain of his followers, and also contemplated what would become of 1901’s inimitable reminiscence, “The Hound of the Baskervilles,” Doyle got his feet wet by offering a tiny Sherlock Holmes story to The Student—a publication of his alma mater, the University of Edinburgh—to help with a fundraising bazaar for a new pavilion for the cricket field. The 1896 issue introduces the piece with glowing pride:

“Dr. A. Conan Doyle, another of our graduates, has contributed an original story of the ‘Sherlock Holmes’ type. We all remember the indignation aroused by the death of the redoubtable detective, a few years ago. This is the only ‘Sherlock Holmes’ story published since then, and we have to offer our best thanks to the writer for his kindness in thus helping us and the Bazaar.”

Though Holmes was still dead, for the time being, “The Adventure of the Empty House” of 1903 proved the ultimate conjuring and capitulation as the lead story in what would become the glorious collection of stories known as “The Return of Sherlock Holmes.”

The Controversy of ‘The Field Bazaar’

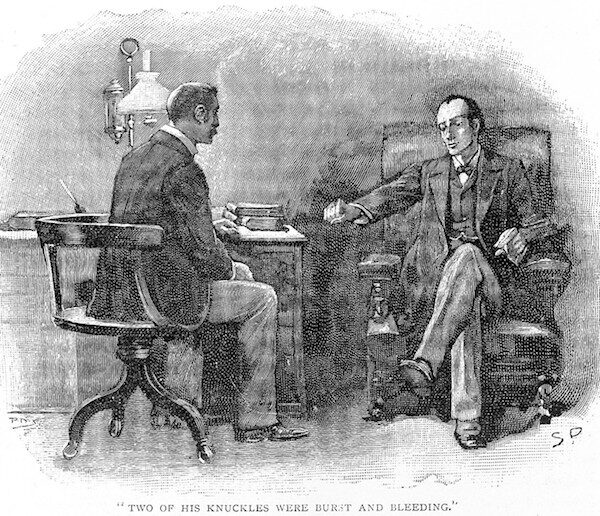

The sketch recounted by Doyle in “The Field Bazaar” is wonderful, even though it is little more than a thousand words long—but it is not without its detractors. In it, we have the great characters themselves just as they are best known and most beloved: at breakfast with The Times and pipes in the sitting room of 221B Baker Street. Sherlock Holmes is up to his old tricks—a term he would certainly repudiate as a logician and no magician.

Using his well-known methods of observation and deduction, Holmes seemingly reads the mind of his frank friend, as Dr. Watson considers whether or not he should assist in an effort by the University of Edinburgh to expand his old cricket club’s field, the very matter that Doyle himself was undertaking in writing the story, giving it a charming self-referential aspect, which is furthered by Holmes’s hypothesis that Watson has determined to recount their exchange as his contribution to the bazaar—again, the very thing that Doyle did.

This vignette, which presents an untold interlude before the Reichenbach affair, is immediately familiar and rings with authenticity. Holmes’s character is as it ever was, and the doctor of Bradshaw and bowler, too, is both as awestruck and self-possessing as ever. Even so, the devotees of the “sacred writings” have long debated the canonical quality of “The Field Bazaar,” with many Sherlockians and Holmesians alike refusing to recognize the piece as worthy of inclusion in the recognized accounts of the career of Sherlock Holmes.

In some ways the tale is too irregular even for some Irregulars, leaving “The Field Bazaar” as one of those contested territories in “The Great Game,” keeping company with other disreputables such as the dubious “The Mazarin Stone” and “The Lion’s Mane.” These latter episodes have endured bristling objections due to their literary quality and glaring inconsistencies with the other published cases, which make them highly suspect as to their authorship and canonical worthiness. While “The Field Bazaar” is not as controversial or outrageous, it tends to be ranked with considerable misgivings.

Of notable mention among the objections to “The Field Bazaar” is Holmes’s strangely rude dismissal of Watson’s title of “Doctor,” even though he did reportedly receive a Doctor of Medicine degree in “A Study in Scarlet.” And while there is evidence that Watson played rugby from “The Sussex Vampire,” there is nothing to corroborate that he ever played cricket. This latter point may be the true smoking gun (a term actually coined by Doyle in “The Gloria Scott”). In its own small way, “The Field Bazaar” challenges Holmes scholars as they test the authenticity and quality of the various cases, sounding the depths of their knowledge to identify so-called apocryphal writings with an eye that “sees and observes,” as Holmes was ever wont to say.

The Mystery of Sherlock Holmes

But the greatest mystery of the Sherlock Holmes stories is, certainly, Sherlock Holmes himself. While the stories of Sherlock Holmes conjure up a solid world with salient iconography—the fireplace, the pipe, the revolver, the violin, the Persian slipper, creeping fog, rushing hansom cabs, stiff corpses, subtle criminals, the outré, the exposé—the endless paradoxes and intricacies of Holmes have given rise to a fascination to crack the case of this extraordinary man, to comb Watson’s memoirs for clues uncovering Holmes’s history and his inmost character, to systematically eliminate the impossible until the truth, however improbable, remains.

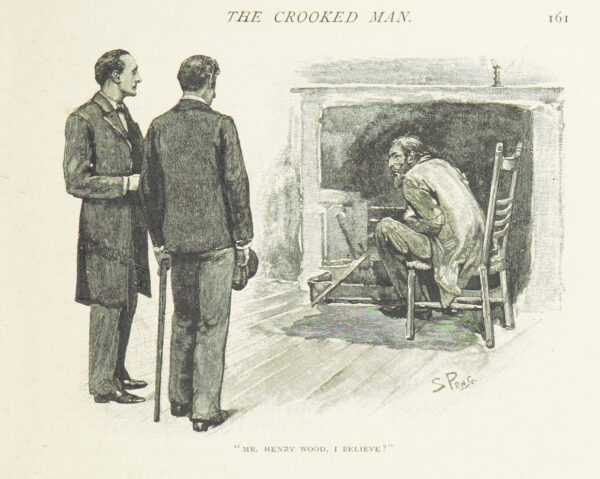

It is not elementary, my dear Watson. (Neither, incidentally, does that immortal sentence exist anywhere in the canon. Holmes’s saying the word “Elementary” in closest conjunction to his saying “my dear Watson” appears in “The Adventure of the Crooked Man,” where they are separated by 52 words.)

Despite such studies and discoveries, Holmes remains a puzzle of a man, full of contradictions and inconsistencies, a problem in and of himself that cries for solution. He is a dispassionate machine commanding a melodramatic kingdom, scientifically replacing drama with science in the most dramatic fashion—both sluggard and swordsman, a civilized Bohemian, a cold-blooded musician—in short, a romantic rationalist. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle gave the world 60 Sherlock Holmes mysteries, but more importantly, he gave the world the mystery of Sherlock Holmes.

The bizarre duality of Sherlock Holmes is precisely why he is an important acquaintance to both young and old readers of today. Holmes is a symbol of everything we are and everything we wish to be. He is lofty enough to be an aspiration, and low enough to be credible. He is an emblem of every man’s desire to wage war with evil and be a noble righter of wrongs—to be a hero.

As a seemingly posthumous tidbit before revealing to the world that Sherlock Holmes was not dead as presumed, “The Field Bazaar” stands as one of the important trifles—if trifles are, as Sherlock Holmes insisted, important—denoting this literary legacy of irresistible shadows. Only a master detective can disperse such shadows, and it is our footsteps that should echo on those 17 steps and knock at the door, seeking illumination, and responding to the call Watson heard in the darkness: ‘Come, Watson, come! The game is afoot.*

*For Holmes scholars: the Case of the Missing Apostrophe.

Sean Fitzpatrick serves on the faculty of Gregory the Great Academy, a boarding school in Elmhurst, Pa., where he teaches humanities. His writings on education, literature, and culture have appeared in a number of journals including Crisis Magazine, Catholic Exchange, and the Imaginative Conservative.

Be the first to comment