There is an old Chinese proverb: If a person does not learn poetry as a child, he or she will not know how to pray as an adult. A more arresting thing could hardly be said, especially in an age when poetry itself asks the question “to be, or not to be?” as it is either shrugged off with indifference or dismissed as unimportant.

Reality must be touched by the miracle of imagination if we are to escape from the straitjacket of logic alone and stay in tune and in touch with the invisible and idealized world that at once perplexes and perfects our logic. As a writer of poetry himself, the theologian and philosopher Thomas Aquinas knew well that, as Robert Burns wrote, “the best laid schemes o’ mice and men gang aft agley,” and that when logic and rhetoric fail, we must look to poetry—though our times threaten to look to it nevermore.

Poetry’s Good Gifts

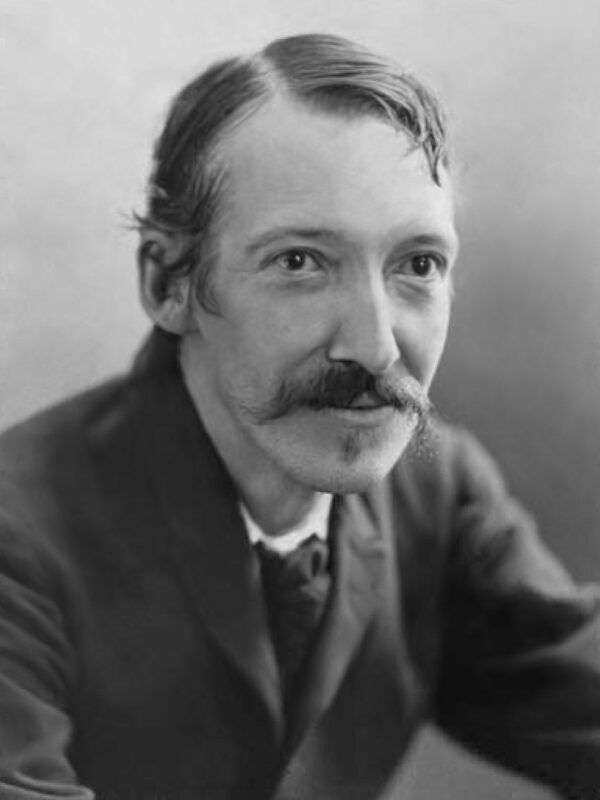

“The world is so full of a number of things,

I’m sure we should all be as happy as kings.”

Considering how much unhappiness there is in the world today, there might be a temptation to dismiss this poem by Robert Louis Stevenson and its ilk as optimistic delusion—which is part of the cause of unhappiness. There is a sad tendency prevalent to view the world as a wasteland rather than a wonderland. This is, perhaps, one of the deepest errors of our time—the error of cynicism.

Keep, modern lands, your storied pomp. What the world needs, what people need is a psychological and spiritual renewal: a renewal of politics, culture, parenthood, education … and poetry. Of all these things that the world stands in need of, however, poetry should stand as a priority.

Without doubt, the world needs pragmatists like scientists and soldiers in the cultural and spiritual war zones to defend good, true, and beautiful things. But in as much as civilization needs professionals, so too does it need poets—and that for a very simple reason. Scientists without poetry can be slaves to systems. Soldiers without poetry can be barbarians devoid of chivalry. A people without poetry cannot be preservers of culture because the charm and glory of faith, life, nature, and art shine with poetry.

Without poetry, death is a bleak finality, instead of one to be not proud. Without poetry, without some intimation or expression of goodness, truth, and beauty, there is less hope of attaining the glorious ends of purpose and peace—whether through war, marriage, work, or any given Tuesday.

Poetry offers that primary knowledge, and thus offers us a window to view and begin to understand a world so full of a number of things. Poems should be lifelong teachers, and they should begin their lessons in the hearts of the young. Once there, they can give satisfying expression to those mysteries of childhood that are beyond a child’s ability to express. And in so doing, poetry can not only begin to introduce children to the outward world and inward emotions, but also give all things their proper place and relation, comparing just the right beauty to a summer’s day.

Dare to Lead

Perhaps the most significant obstacle to providing today’s children with the experience of poetry is that many of today’s parents and teachers have not had the experience of poetry themselves. It is never too late to mend.

Look on her works, ye Mighty, and do not despair. Poetry—that art which meditates on beauty, rest, perfection, and a small participation in the essence of things—is good for grown-ups too. No matter how old you are, or how busy you are, it is always important to be reminded of the aim of beauty and mystery that all our distracting means are for the sake of.

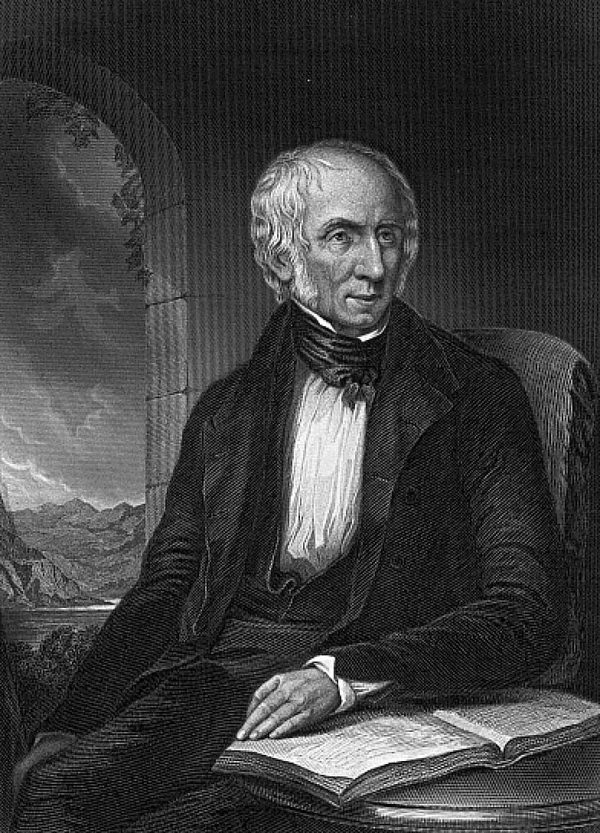

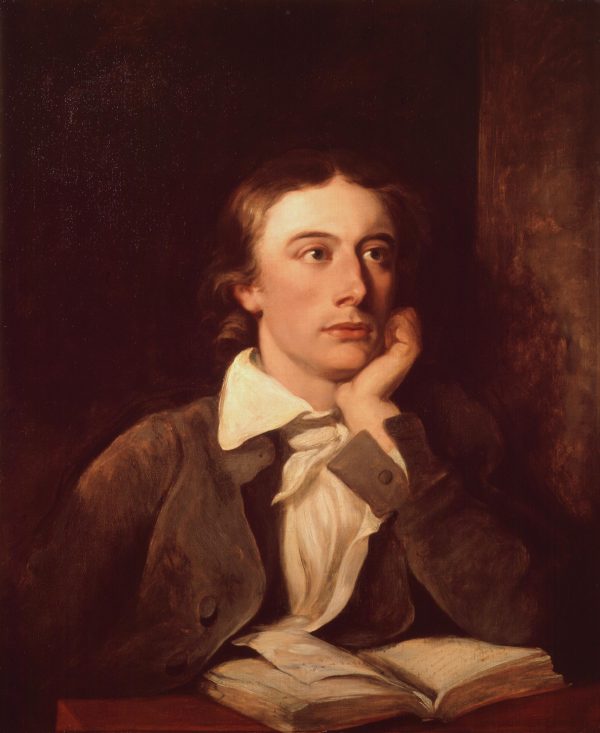

If you never thought about the importance of poetry, do not, by any means, let this article convince you. Go to the source in the bliss of solitude. Take the time. Read Shelley, Keats, and Byron. Read Wordsworth and Poe. Read the Psalms. Read Homer, Virgil, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Coleridge, and Hopkins. Write your own book inscriptions and Christmas cards to your loved ones in verse. Be attentive of eye and ear and heart. They also serve who only stand and wait.

Immerse yourself. Dare to engage the fearful symmetry. And above all else, enjoy it. Take the time. No parent or teacher can give their child or charge what they do not have. No pupil will take to heart what is brushed off by their parents or teachers. If parents and teachers want their children to be virtuous, they must be virtuous first. If parents and teachers want their children to be kind and hardworking, they must be kind and hardworking before them. If parents and teachers do not read and savor poetic works, neither will their children.

Let us, then, be up and doing. The first step to giving your loved ones the gift of poetry is to love it first yourself. The rhythms of poetry reflect the rhythms of creation, of life, and the human heart. They put profundities in the mouths of babes, fortifying them for those times when, as adults, they will cry out from the depths.

The reinforcements of beauty must not be lost. Like the coming of spring, the world will be saved by beauty, as Dostoevsky wrote. And a line of poetry may make all the difference in a person’s salvation. In the immortal words of John Keats:

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

life on Feb. 23, 1821. (Public Domain)

A Good Beginning

There is nothing like a poem held in the heart, like a fire in the hearth, to give the first and final context of earthly experience. There are many excellent poems—some of the best ever written in English, in fact—that are not hard to memorize. And they should be memorized, and brought along on the adventure of our lives, and taught to children, grandchildren, and students.

This article begins a series presenting a few very memorable poems. They are not long or difficult. It doesn’t take long to learn them, nor is it difficult to recite them on a walk, in the car, at the table, or in the living room. Take this series to heart. Teach your young minds and hearts the poems that will be presented in these pages and plant the power of poetry in their lives, and perhaps even the power of prayer and meditation.

They will be only a beginning, true, but any good poem is a good start. And that is one of the good things about poetry. It is always setting out on the right foot, seeking afresh, trying to arrive at some end, some destination, that we all have some inkling of but that we must ever strive for in this life even if we don’t get there fully.

And this is the paradox of all good poems and what makes poems good—that they must fail to capture their subjects, for their subjects are worthy of poetry only if they cannot be captured. And thus is the lovers’ elusiveness alive between the poem and the primal, bringing forth the truth that there are tears in things—tears both of inexpressible sorrow and inexpressible joy.

But even though they fail, poems such as the ones to come will not fail those who commit their hearts to poetry by committing poetry to heart. It is in the striving that poetry rejoices, and so must we.

The series “What Good Is Poetry?” looks at poems that, once memorized, bestow a gift: an antidote to the cynicism of our age.

Sean Fitzpatrick serves on the faculty of Gregory the Great Academy, a boarding school in Elmhurst, Pa., where he teaches humanities. His writings on education, literature, and culture have appeared in a number of journals including Crisis Magazine, Catholic Exchange, and the Imaginative Conservative.

Be the first to comment