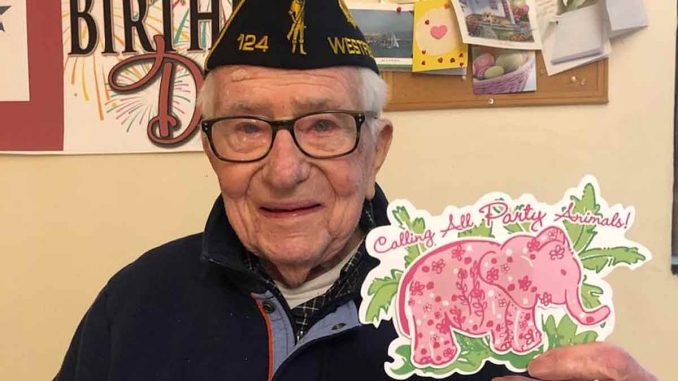

U.S. Army Air Corps veteran John MacKay survived World War II, having served in Burma, one of the most disease-ridden campaigns of the war in the Pacific. After service, he married the love of his life and settled in Westfield, Massachusetts, to raise five daughters and work as a high school guidance counselor.

But the 99-year-old is again in a fight for his life, this time in the contagious confines of the Soldiers’ Home in Holyoke, Massachusetts, a hotbed for the coronavirus in the state. He, along with 79 other residents, have been diagnosed with COVID-19, while another 81 veterans at the facility have died from the illness.

For the families of these veterans, the experience has been a nightmare — an ongoing battle to get any news from the place their loved ones have lived for months or years.

Related: Nearly 70 Dead in ‘Horrific’ Outbreak at Veterans Home

“The communication is absolutely deplorable. We get these emails saying, ‘Call the family number — you can Zoom. You can Skype.’ But you can’t get an answer. It just rings and rings. The frustration level is absolutely terrible,” said MacKay’s daughter, Betsy Crupi. “People have dropped the ball.”

Farther south, at the Paramus Veterans Memorial Home in New Jersey, Tom Mastropietro, an Army veteran who served in the Korean War, also was diagnosed with the coronavirus. He appeared to beat the devastating disease, eating breakfast and moving about unaided on April 11, his family was told.

But like much of the news related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the facts of Mastropietro’s case were muddled. In the chaos at the home as the infection spread, a mix-up occurred: Mastropietro actually died that day, his identity swapped with another COVID-19 patient at the home who survived, according to a report on NorthJersey.com.

“I inquired about the coronavirus and was told there were no cases,” Steve Mastropietro told the publication. “Looking back, I’m sure there were coronavirus cases, but no one had been tested.”

Across the country, families of veterans living in state-run veterans nursing homes have received similar devastating news. But just how many veterans are affected in 157 facilities run by the states is unknown. Fewer than a dozen states publish detailed information about COVID-19 cases and deaths in long-term care facilities by individual homes. And neither the National Association of State Veterans Homes, an advocacy group, or the Department of Veterans Affairs track the data.

“State veterans homes are run by individual states, not the federal Department of Veterans Affairs. If you have questions about state veterans homes, we refer you to the individual states,” VA spokeswoman Christina Noel said.

The devastation has been so great in some state veterans homes, a group of U.S. senators wrote the Government Accountability Office on Tuesday, calling for an investigation into the VA’s oversight of them.

“Given the importance of state veterans homes in VA’s overall portfolio for providing institutional care to veterans, and our ongoing concerns about VA’s role monitoring states’ operation of these facilities, we would like GAO to conduct a more detailed examination of VA’s oversight of … quality of care,” wrote Democratic Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey of Massachusetts, Jon Tester of Montana and Bob Casey of Pennsylvania.

The Massachusetts home where MacKay lives has been the hardest hit among state-run veterans’ facilities. But at least 230 other veterans have died in these homes in 16 states, according to a review of media reports and state databases.

Those numbers are not included in the VA’s daily updates of COVID-19 infections and death data in its own facilities.

As of Wednesday, COVID-19 had killed 594 veterans in VA facilities and infected nearly 10,000 receiving care from the Veterans Health Administration. An additional 185 veterans have died, according to reports sent to the VA, but how many of those were in state-run homes has not been disclosed.

The senators want more clarity on the impact of COVID-19 on the veteran population. Warren has been calling for a coordinated effort to collect and publish the data.

While the VA is not directly responsible for state-run veterans homes, it pays 100% of the cost of care for veterans living in the homes who have service-connected medical conditions that require full-time care. The VA also is required to inspect the homes each year to ensure they meet department standards.

In July 2019, however, the GAO faulted the department for not adequately monitoring the contractor hired to run the inspections. The GAO also said the VA was not transparent with its assessments of the quality of care provided by state veterans homes. The office made several recommendations to the VA about oversight that included increased contract monitoring, and clarity and transparency on deficiencies found at the homes.

The senators asked the GAO to provide an update on the VA’s response to the recommendations, saying failure to implement them may place veterans at risk.

“The recent deaths of veteran residents and other care challenges at state veterans homes during the COVID-19 public health emergency remind us that VA’s implementation of these recommendations would contribute toward improved care quality at these facilities nationwide and better inform veterans and their families about the best care options,” they wrote.

State veterans homes date to the aftermath of the Civil War, when they were created to house veterans injured and left homeless as a result of the conflict. In addition to nursing home care, many of the state homes provide housing for indigent veterans and adult day care programs.

Since the first COVID-19 outbreak at a nursing home killed 37 residents in Kirkland, Washington, long-term care facilities have borne the brunt of the illness, making up 18% of all coronavirus deaths in the U.S.

The first sign of the potential impact at a state-run veteran home came in mid-April, when a sixth veteran died at the Oregon Veterans Home from the disease. Another 15 tested positive.

This month, in New York, the Long Island State Veterans Home reported 53 deaths, while the St. Albans State Veterans Home in New York City recorded 33 deaths.

In New Jersey, 69 veterans have died at the home where Mastropietro lived, while an additional 54 veterans have died in two other state-run veterans homes.

And in Alabama, at least eight residents have died at the Bill Nichols State Veterans Home in Alexander City.

The GAO warned of shortcomings within both VA nursing home facilities and the state-run homes, citing 576 “deficiencies” at 126 VA homes between 2012 and 2017 and 192 deficiencies at 148 state veterans homes during the same time frame.

Those deficiencies included instances where patients were not adequately treated for bedsores, infection control was found lacking, immunization protocols for influenza and pneumonia were not followed or the facilities failed to adequately support residents with their hygiene, grooming or other activities of daily life.

“By not performing observational assessments of state veteran homes inspections, VA does not know whether, or to what extent, VA’s contractor needs to improve its ability to identify [their] compliance with quality standards, which increases the possibility that quality concerns in some [homes] could go overlooked, potentially placing veterans at risk,” the report noted.

Last month, the VA sent nurses and other employees to assist at the state-run homes in New Jersey, Massachusetts and elsewhere.

“We are providing, when the governors request it, we can go in and manage, clean and provide resources. In New Jersey, two of three homes are on the verge of failing. Same thing happened in Massachusetts. What I told the governors was, if they need us, call us,” VA Secretary Robert Wilkie told Military.com on April 16.

Last month, the White House also announced it is requiring nursing homes to report any COVID-19 cases at their facilities to residents and families.

Crupi said that while she does not want the issue politicized, the response from the administration, the VA and the state of Massachusetts has come too late.

“To think that so many people died. Who is accountable? These veterans were on the front lines for their country yet no one has had their back,” she said.

Neither the Holyoke home nor the Paramus home responded to a request for comment.

In mid-April, Mark Piterski, deputy commissioner with the New Jersey Department of Military and Veterans Affairs, gave a statement to NorthJersey.com.

“We are devastated that this error occurred and we offer our most sincere apology for the mistake in the notification of their father’s passing,” Piterski said.

Piterski, who oversaw the state’s three homes, where 103 veterans have died, resigned April 28.

John MacKay will turn 100 on May 15. His family, which planned his birthday party months ago, has decided they will travel to the Holyoke facility with posters and balloons to celebrate long distance. Whether he will make it or the family will be allowed to get close to the facility is uncertain; Massachusetts State Police have blocked all access to the campus, Crupi said.

She said it is not fair that her father, who as recently as February requested his favorite beverage, a seasonal Sam Adams, at a restaurant, should be alone.

“He’s 99. He’s lived that long because he’s taken care of himself. He was turned away twice from a hospital when his oxygen levels dropped because of his age. Who are they to decide who lives and who dies?” she asked.

— Patricia Kime can be reached at Patricia.Kime@Monster.com. Follow her on Twitter @patriciakime.

Read more: VA Gets COVID Relief Money to Combat Homelessness

© Copyright 2020 Military.com. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Be the first to comment