It was the early afternoon of June 17, 1876, when a bullet ripped through Cpt. Guy Henry’s cheek.

For several hours, he was one of more than 2,000 people fighting in the largest battle of the Plains Wars. The fighting involved the United States government, committed to confining the Indigenous peoples of the continent to reservations, and the Cheyenne and Lakota who continued to resist.

Henry, a cavalry officer and veteran of the Civil War, was treated for the nearly fatal wound at a hospital triage unit near Rosebud Creek, just east of what is today the Crow Indian Reservation. The bullet to his right cheek cost him an eye, but he would survive. While a surgeon sewed his face back together, according to his account of the battle, he could hear the sound of shovels hitting the earth, digging a grave for the nine U.S. soldiers killed in the Battle of the Rosebud.

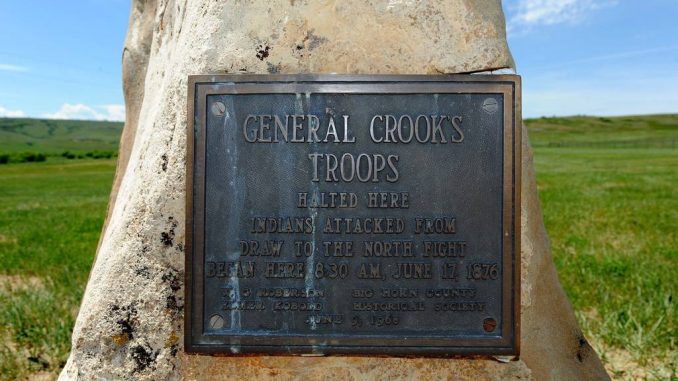

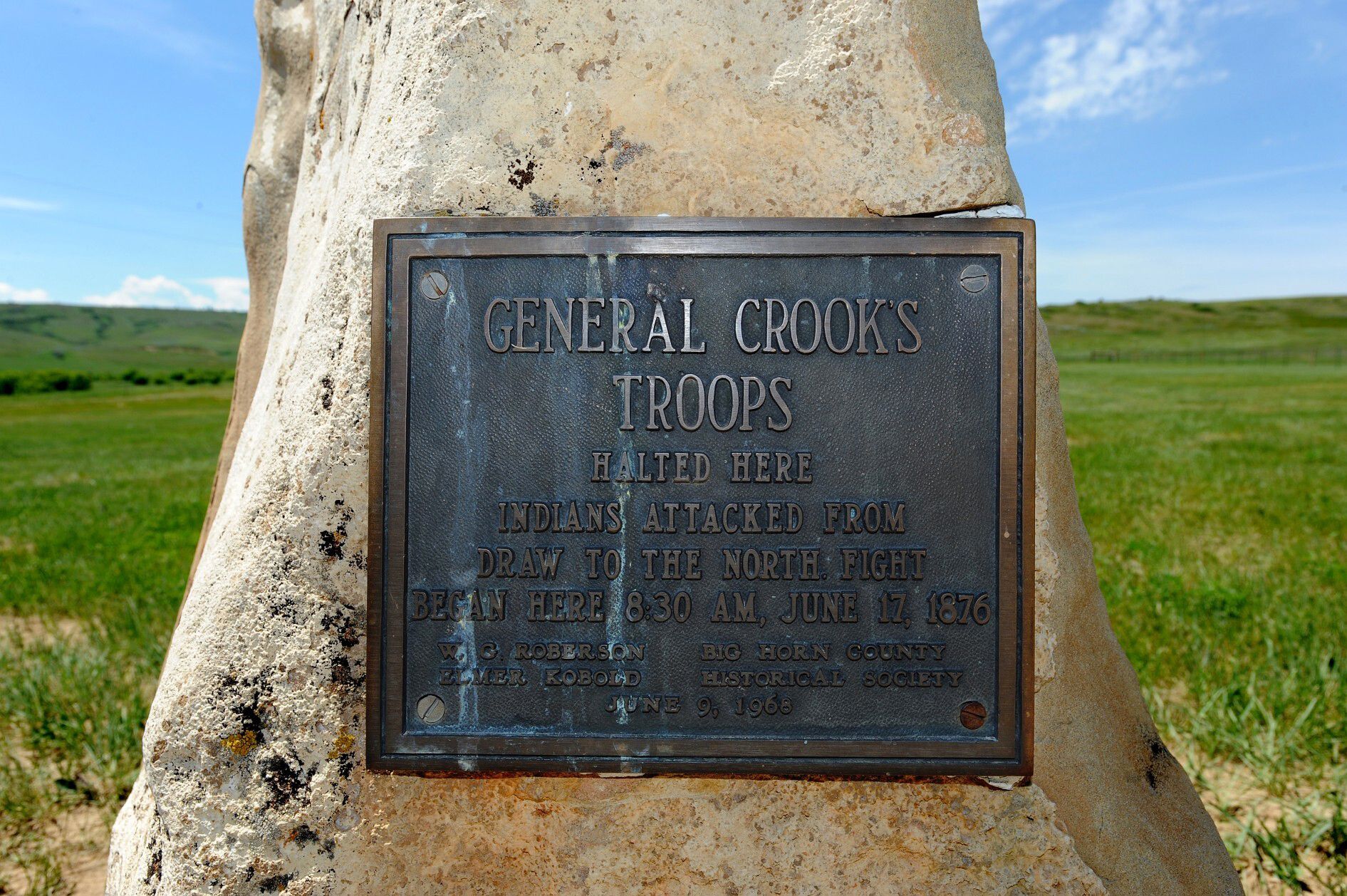

To prevent their bodies from being discovered, men under the command of Gen. George Crook built a massive fire over the grave. Once the fire was snuffed out, they rode horses over the burned earth and covered any trace of who laid below.

With much of the battlefield remaining largely unchanged over the next 145 years, a team of researchers conducted a survey last week trying to find those nine men.

“It’s one of the Rosebud mysteries. Where are the soldiers buried?” said Rosebud Battlefield State Park Manager Raymond Schell.

The 3,052-acre park, located about 50 miles southeast of the Little Bighorn Battlefield, contains major landmarks from the conflict, along with several sites that date back millennia before the first Europeans stepped onto the continent. The sandstone cliff facing the northeast is coated with petroglyphs, and also served as a buffalo jump.

In the summer of 1876, Gen. Crook led more than 1,000 infantry, cavalry and civilian packers into the Montana territory. He was riding out of Sheridan, Wyoming, one of three invading columns sent by the federal government to strike at the bands of Lakota and Cheyenne who shirked orders to live within a reservation. Joining Crook were hundreds of Crow and Shoshone scouts.

Those fighting under Crook made their way to Rosebud Creek, traveling lightly with only a few days’ worth of rations. They expected to find a village along the creek to attack, with the violence limited to brief hit-and-run encounters. There was no village, and on the morning of June 17, anywhere from 700 to 1,500 Northern Cheyenne and Lakota led by Oglala Chief Crazy Horse and Cheyenne Chiefs Two Moon, Young Two Moon and Spotted Wolf sprang on Crook’s men while they rested their horses.

For the next several hours, the battle occurred over a three-mile front in volleys that saw soldiers fending off repeated charges. Although they managed to hold their ground against the Northern Cheyenne and Lakota, one army officer later wrote, “They proved then and there that they were the greatest cavalry on earth.”

With the shooting over by 2:30 in the afternoon, Crook counted nine of his men dead, along with a Shoshone scout. The Sioux and Northern Cheyenne, who refer to the battle as “Where the Girl Saved Her Brother,” fought the federal troops to a standstill, and accounts of their total losses vary. The same bands that attacked and stalled Crook at Rosebud Creek would overwhelm Lt. Colonel George Custer just eight days later at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

“It’s a poignant story as all of the stories about that time are. It’s about the displacement of people, and the fight to survive,” said Doug Scott, an expert in forensic and military archaeology with Colorado Mesa University. He was one of a handful of people who searched the area around Rosebud Creek for the nine dead soldiers.

Scott, who previously studied the Little Bighorn Battlefield for the National Park Service, has visited the Rosebud Battlefield several times. Prior to last week, he led a group who surveyed a portion of the battlefield in 2018 burned by a wildfire, picking up bullets, casings and other artifacts that dot the undulating landscape.

With funding from the Lee and Donna Metcalf Charitable Trust, the hunt for the soldiers’ grave is one of several projects intended to clarify the events of a day often overshadowed by the obliteration of Custer and his 263 soldiers. The search is the result of a partnership between Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, tribal officials, the State Historic Preservation Office and faculty with Colorado Mesa University.

“What we’re trying to do is put together the physical history of the battle and see how it fits with Native American oral accounts and written records. We look at it as a crime scene, quite in the literal sense … No line of evidence is perfect, but when you have the three and you weave them together, you get a better picture of what happened,” Scott said.

“It feels a little bit like being a farmer,” said Jarrod Burks with Ohio Valley Archaeology, Inc., a private firm based out of Columbus, Ohio, contracted to spearhead the search for the soldiers with ground-penetrating radar and magnetometry instruments.

Burks has experience in surveying POW camps and mass graves throughout Europe and Africa. This is the first time his work has brought him to Montana. He and his colleague, Alexander Corkum, crisscrossed through the grassy areas that border Rosebud Creek in an ATV, a magnetometer in tow and collecting thousands of gigabytes of data. Ohio Valley Archaeology, Inc. will also produce 3D models of several petroglyphs carved into the buffalo jump, a digital preservation of markings that will eventually vanish due to erosion.

“The fortunate thing about this site is that it’s basically unchanged besides some farming, whereas back in the East you have to wade through centuries of buildings,” Burks said.

The search team looked over an area of about 31 acres, an area based on first-hand accounts of the aftermath of the battle, like that of Cpt. Henry. Although their equipment couldn’t detect an obvious grave or bones, it could pick up anomalies that might suggest a trench or pit dug into the earth. Although the team located several anomalies, they didn’t find any soldiers.

Over the next several weeks, Burks and Corkum will sift through that data, providing what Scott called a “fine filter” that might suggest a gravesite.

“We could be in the wrong spot, that’s one real possibility. The graves could have been exhumed at some point in the past. Aside from maybe someone digging into the grave, it may have been scavenged, and the bodies scattered. Bear and coyotes are excellent scavengers. We don’t know yet and we’ve still got a lot of research to do,” Scott said.

Rachel Reckin, the heritage resources program manager for FWP, said there is no intention to move or even touch the nine soldiers. Should research lead to the location of their bodies, a marker will be placed at the site.

Be the first to comment