News Analysis

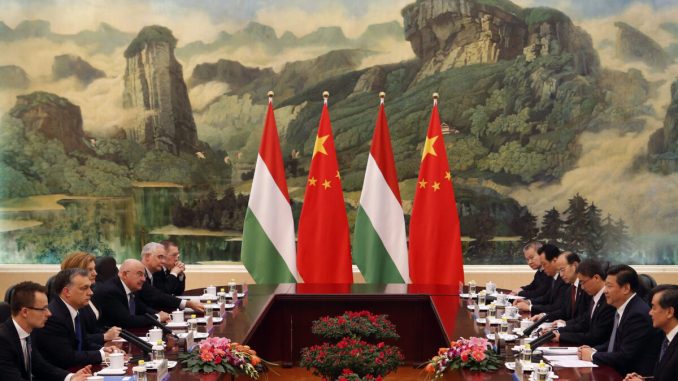

As the free world unites to condemn and penalize the human rights violations and aggressive expansion of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), one European country is moving against the tide.

Hungary has demonstrated a firm pro-CCP stance in a series of recent events, after the European Union, the United States, the UK, and Canada announced sanctions against China over the genocide of Uyghur Muslims on March 22. The Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto accused the sanctions of being “pointless, self-aggrandizing, and harmful.” Of the 27 EU members, Hungary was the only country that voted against the sanctions.

Three days later, Budapest hosted China’s defense minister for an official visit. Between March and May, Hungary blocked the EU’s efforts to sanction and condemn the CCP four times.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping was so pleased with Hungary’s defense of China that he personally called Prime Minister Viktor Orban on April 29 to commend his “great contributions to maintaining the China-Europe relationship.”

Orban deserves the favor. He has embraced Xi’s signature Belt & Road Initiative (BRI, also known as One Belt, One Road), the backbone of China’s road map to global hegemony. Hungary signed a BRI memorandum with China in 2015, the first European country to do so.

Since then, Hungary has willingly taken in almost every item that BRI sells, from a high-speed railway, machinery, chemical manufacturing, and transportation, to Chinese education, movies, and even CCP virus vaccines, and much more. By April 2019, China had invested $4.5 billion in Hungary, the highest in Europe, according to Orban. The official BRI site fondly calls Hungary “the pioneer of Belt & Road.”

Of course, the BRI is no charity. The CCP has invested heavily in Hungary for more practical reasons than friendship. The heavy loans, the growing reliance on RMB, the labor supply, and the local employment have made Hungary increasingly dependent on China. The education programs and universities imported from China will seed and nurture communist ideology in the country.

To the CCP, the benefits of controlling Hungary are clear. Hungary’s location makes it a good springboard for China to penetrate the European market from an economical point of view. China also uses Hungary to acquire high-tech and know-how from European countries. Financially, by bringing an RMB clearing service into its border, Hungary is helping accelerate the globalization of RMB.

But what pleases the CCP the most is probably the political gains. Hungary just proved itself a loyal ally to the CCP in the recent vetoing of the EU’s sanctions on China, regardless of China’s long track record of atrocity that the rest of the world is trying to stop. Hungary’s support was broadly reported by Chinese media to convince the Chinese people that the sanctions are malicious conspiracies against China and that the persecution and genocide were mere rumors.

BRI Debts Weaken Sovereignty

The total amount that Hungary borrowed for BRI projects is unknown, but what has been announced is already quite alarming: $2.4 billion for the railway update; $1.6 billion for the construction of the Fudan University Budapest campus; $426 million to the Hungarian Electricity Company in 2021; and $121 million for the Kaposvar photovoltaic power plant. In 2016 and 2017, Hungary issued $310 million worth of RMB bonds in China.

Hungarian critics say the loan on the railway project will generate interest of between $500 and $800 million. “It will take between 130 and 2,400 (!) years to make the project profitable for Hungary,” said Zoltan Voros, assistant professor at the University of Pecs’s Department of Political Science and International Studies. Voros also pointed out that Hungarian businesses are excluded from most of the procurement process.

The high BRI debts are concerning for many reasons. In April 2021, “when the small nation of Montenegro approached the European Union for help paying off a nearly $1 billion loan to China’s Export-Import Bank (EXIM), borrowed to finance the construction of a large highway project, alarm bells were raised across Europe,” said Jennifer A. Hillman, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). The debt for the BRI project was 103 percent of Montenegro’s GDP.

Montenegro was not the first country that fell into the BRI debt trap. China has lent $461 billion to BRI projects since 2013, likely excluding an equal amount that’s not publicized. Most of China’s BRI loans have gone to high-risk countries like Pakistan, Iran, Nigeria, and Venezuela as if credit rating was not even taken into consideration in China’s lending decisions.

Defaulting on BRI debts can be a catastrophe for these countries, as demonstrated by Sri Lanka’s fiasco: When the island nation was unable to meet its debt obligations to China for the $5 billion BRI loan, Sri Lanka had to hand over to China a 70 percent share of its deep seaport at Hambantota for 99 years for $1.12 billion. Fearing similar consequences, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Burma, Pakistan, and Sierra Leone have all subsequently decided to cancel or downsize their BRI projects.

Since the CCP virus hit, more countries are likely to default. China has received a wave of applications for debt relief from crisis-hit BRI, according to the Financial Times.

Corruption poses another concern. Hong Kong’s former home affairs secretary Patrick Ho Chi Ping was sentenced to three years in jail in March 2019 for paying off top officials in Uganda and Chad to support BRI projects. Ho allegedly offered a $2 million bribe to Idriss Deby, the president of Chad, in 2014 to obtain valuable oil rights from the Chad government. The $2 million cash was concealed in a few gift boxes, which were offered to President Deby at the end of a business meeting. Ho also allegedly wired a $500,000 bribe to Sam Kutesa, the minister of foreign affairs of Uganda, and schemed to pay a $500,000 cash bribe to Yoweri Museveni, the president of Uganda. Ho’s case begs scrutiny over how other risky BRI projects were approved.

Major Acquisitions Help China Gain Industry Dominance

Over the past decade, China has provided billions of dollars of subsidies to state-owned companies to acquire Western manufacturers and build factories abroad, according to The Wall Street Journal. The acquisitions not only allow China to roil the global market with low-price goods but also to dodge anti-dumping tariffs in the West. In Hungary, China made several big acquisitions, including the $246 million purchase of Invitel, Hungary’s second-largest corporate communications provider.

The chemical industry is one of the pillars of China’s global expansion strategy. MDI is a chemical broadly used in architecture, automotive, appliance, and apparel manufacture. China had long coveted the market due to the high profit and broad market, but the technology was a challenge.

In 2011, China’s Wanhua Chemical Group acquired Hungary’s BorsodChem (BC) for $1.6 billion and surpassed Dow and BASF to become the world’s largest MDI supplier.

Chinese media depicted the acquisition as a big favor to BC and Hungary. CGTV, the English branch of the CCP mouthpiece Xinhua, quoted the local mayor’s adviser saying, “If Wanhua as an investor did not come to this city, then this would have caused a big problem for this city.”

The truth is that Wanhua imposed the acquisition on BC. When BC was deep in debt due to the 2008 global financial crisis, Wanhua sought to purchase the company, but BC’s owners Permira and Vienna Capital refused the acquisition.

Wanhua would not back off, because the acquisition was an important step for pushing Belt & Road to the world through Europe. By purchasing BC’s mezzanine debts and obtaining BC’s equity and calling options, Wanhua eventually acquired BC’s full ownership.

Chinese propaganda has complimented Wanhua as “the Huawei of the chemical industry” for its size and its ambition to dominate the industry globally. Wanhua now makes 24 percent of the world’s MDI and is now trying to expand into U.S. territory. Its initial attempt to build facilities in St. James Parish, Louisiana was thwarted by local residents’ heated objections in 2019, but the company said it still has aspirations for a U.S. MDI facility.

Education Partnership Invites Communist Ideology

While BRI is mostly known for its infrastructure projects, China built in a soft power pillar to promote communist ideology in BRI countries through Confucius Institutes and talent exchange programs.

In Hungary, this was taken to the next level. Hungary opened its fifth Confucius Institute (CI) in November 2019 following a wave of closures of CIs by colleges around the world. In the United States, the number of has CIs shrunk from over 100 to less than 50 in the past couple of years. Many European countries followed suit, including Denmark, Sweden, France, and the Netherlands.

As if to protest, Hungary signed an agreement with Shanghai-based Fudan University on April 27 to set up a campus in Budapest. The campus is expected to hold 5,000 to 6,000 students and about 500 professors. Hungary is taking a $1.56 billion loan from China’s state-owned China Development Bank to pay for the construction, following the typical BRI funding model. The campus will be built mostly by Chinese companies and Chinese workers.

All Chinese schools are tightly controlled by the CCP and are under strict CCP censorship. Various Hungarian politicians including Budapest Mayor Gergely Karacsony raised concerns that bringing the Chinese state university to the country will be a national security risk.

First BRI Project Still Pending 8 Years After Announcement

The first BRI project in Hungary was the Budapest–Belgrade 220-mile high-speed rail line. The $2.98 billion project was said to be the first stage of the planned Budapest–Belgrade–Skopje–Athens railway that connects the China-run Piraeus port in Greece with the “heart” of Europe.

The plan has since changed several times without much explanation. When Hungary and China announced the project in 2013, the plan was to complete the construction and upgrade in 2018. In 2017, China Daily reported that the rail line construction would start in November 2017, and complete in around two-and-a-half years.

Nothing happened. Then in April 2019, Hungary announced that a contract would be signed by May 25 for the upgrade of the country’s section. The project was now reduced to a 100-mile upgrade, only 45 percent of the previously announced length. The cost went down, but was only reduced by 3 percent to $2.8 billion, and the duration was extended to five years, with expected completion in 2025. The portion that’s funded through Chinese loans remains 85 percent. No further update has been made since then.

Pingping Yu has been a writer, translator, and researcher for The Epoch Times since 2007. She covers a variety of topics related to China, with a strong focus on human rights, economy, and business.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.

Be the first to comment