In their small riverside dairy, cheerful cheesemakers Katherine and John Spencer are unlikely standard bearers for one of the world’s oldest food processes.

The couple are the last cheesemakers in their village—which wouldn’t be very remarkable if that village wasn’t called Cheddar. Among the leafy lanes and rolling farmland of Somerset, in England’s rural West Country, Cheddar is the birthplace of one of the world’s most famous and popular cheeses.

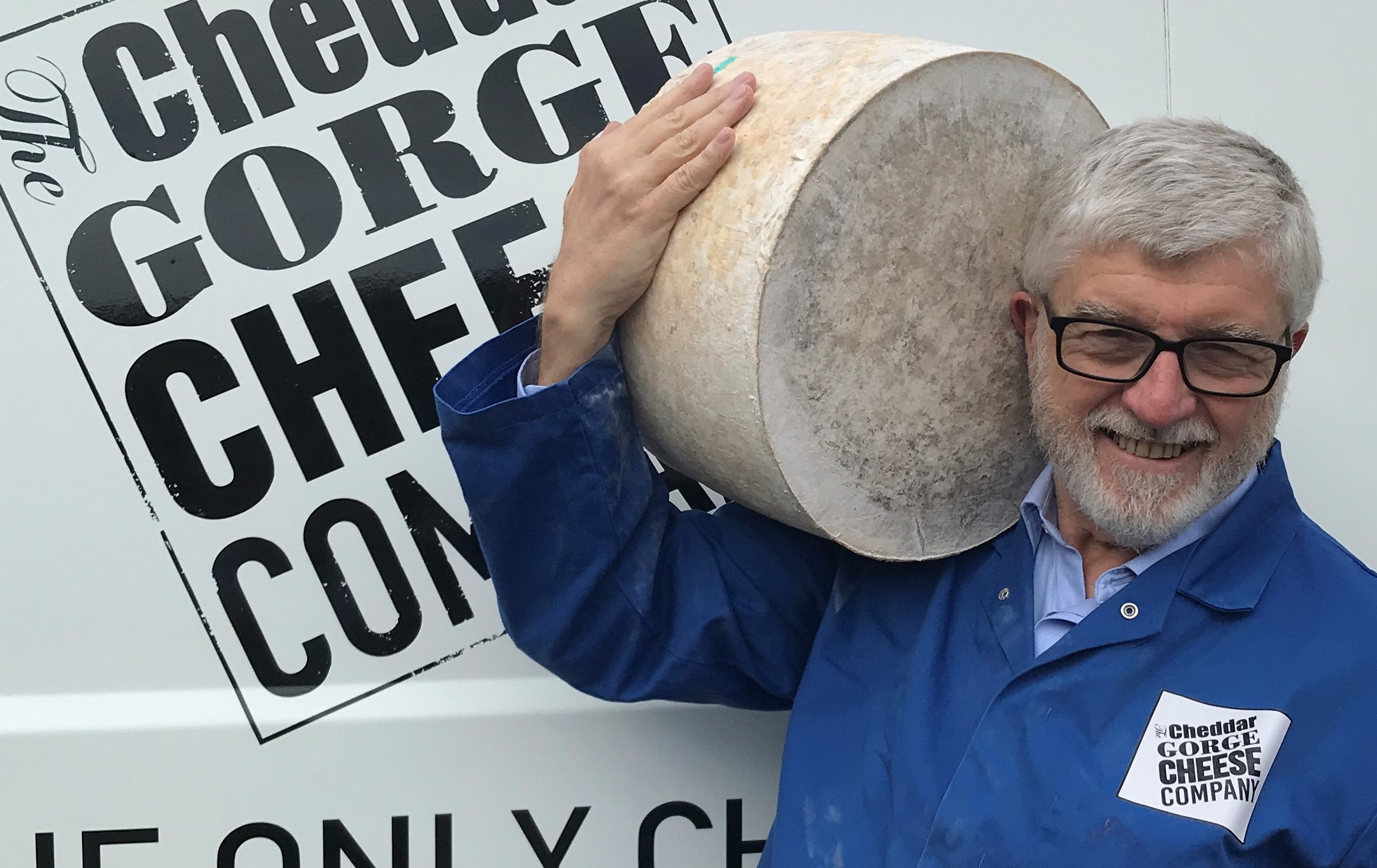

Cheesemaking here had almost disappeared, as mass-produced industrial products swamped the market. With their Cheddar Gorge Cheese Company, the Spencers are fighting back.

Riverside Cottages and Ancient Caves

Seeing Cheddar’s pastel-painted riverside cottages and 14th-century church, it’s hard to think of this as a global fulcrum in the story of cheese. Even in England the village is more famous because of the spectacular limestone cliffs of Cheddar Gorge, once voted the country’s greatest natural wonder.

The Gorge’s rocks are riddled with caves where prehistoric humans lived. Britain’s oldest skeleton was found here. The caves inspired Tolkien’s Helm’s Deep in The Lord of the Rings and are now a major tourist attraction. More importantly for food lovers, these caverns, part of the vast estate of local aristocrat Lord Bath, are important ingredients to the story of cheese.

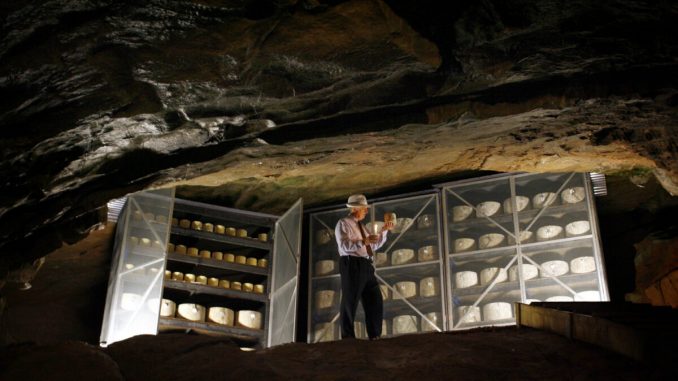

Somerset has long been a thriving center of dairy farming, with its lush, green, south-facing pasture adding creaminess to the milk from its herds. Right next to the village was a perfect natural fridge for maturing cheese: the constantly cool, humid caves. Some food historians believe cheese could have been developed here since the Romans. As part of their battle to be truly authentic, the Spencers persuaded Lord Bath to allow them to mature contemporary cheddar in the caves too.

The couple, already both enthusiastic cheese experts, met on a visit to a Brie factory in France. They set up their dairy in Cheddar in 2003 with an idea to produce high-end traditional cheese.

“We saw this as an opportunity to make our own cheese together,” said Katherine. “We both learned about cheese from careers in the dairy industry, and it combined all our expertise and experience. We wanted to concentrate on small-batch production, making authentic cheddar by hand, with local raw milk from one farm.”

“Supermarkets wouldn’t pay the price for this sort of artisan product, and would want far bigger quantities than we wanted to produce,” she said.

Handmade, Cave-Aged

From a viewing gallery at the Spencer’s dairy, today’s visitors can see the ancient process.

When milk curdles under gentle heating, it separates into liquid whey and jelly-like curds. Cheesemaking involves draining the whey and pressing and drying the curds. Cheddar’s medieval cheesemakers’ refinement of this process was repeatedly chopping the curds into slabs, stacking them, and chopping again, a method called “cheddaring.” The result is a denser texture and tangier flavor. John, Katherine, and their three cheesemakers still “cheddar” by hand in a long open vat.

The resulting chips of curd are then salted and pressed into a mold. Traditional makers like the Spencers wrap the cheese in cloth, allowing it to breathe and interact with bacteria, while factory makers might wrap with plastic, leading to more rubbery, soapy textures and less complex flavors.

The Spencers’s cheeses are substantial—around 57 pounds—and are “long-matured,” meaning they’re stored in a controlled temperature and humidity environment for between six and 24 months. Their longer matured “Vintage Cheddar” develops stronger flavors. The Spencers mature some cheese in purpose-built stores, others in the nearby caves.

“The environment in which the cheese is matured has a remarkably significant influence on the flavor,” Katherine said. “Our cave-matured cheddar has been an outstanding success due to its complex flavor, aroma, and texture. It’s unique.”

Critics seem to agree. In fact, the Spencers won “Best Cheddar” in the 2008 World Cheese Awards, and in 2019, their 2-year Vintage Cheddar and 1-year Cave Matured Cheddar were shortlisted for the Great British Food Awards.

“As a small artisan maker competing against producers from all over the world, we are all thrilled,” said John. “It does seem fitting that authentic cheddar has returned to its birthplace.”

Mass Production

Records show that cheddar was already famous in 1170: There are bills from King Henry II buying 10,420 pounds of it.

During the Second World War, however, British farmers had to make one single cheese, nicknamed “Government Cheddar,” due to the war economy. Fewer than 100 artisan cheesemakers remained after the war.

In the unregulated days before globalized production, cheddar was considered “authentic” if crafted within 30 miles of Wells Cathedral in the heart of Somerset dairy country (the glorious church is just nine miles from Cheddar). Somehow this evolved into an EU regional food designation for “West Country Farmhouse Cheddar,” which applies only to cheddar traditionally made at a single farm anywhere within a vast area of western England. Post-Brexit, it’s unclear what regional protection, if any, will apply.

But despite the obvious link to its birthplace, normal “cheddar” cheese can of course be made and sold anywhere. Cheddar is now mass-produced in factories from Australia to the United States, but it often became a bland-tasting victim of its own success.

“The name ‘cheddar’ has never been protected, so [it] can be made all over the world,” said Katherine. “One day we’d love to challenge this—but no doubt we would need a team of lawyers and researchers. Perhaps we’ll just concentrate on making cheese instead.”

Visit CheddarOnline.co.uk for more information—and to buy cheese. It is shipped to the UK and most of the EU. Before the pandemic, John visited the United States to look for reliable importers, but plans have been put on hold temporarily.

Writer Simon Heptinstall has lived and worked all his life in England’s West Country region, including editing its newspapers, writing its travel and food guides, and becoming a trained cider-maker. His writing can be found in BBC Countryfile, the Times, and the Daily Mail.

Be the first to comment