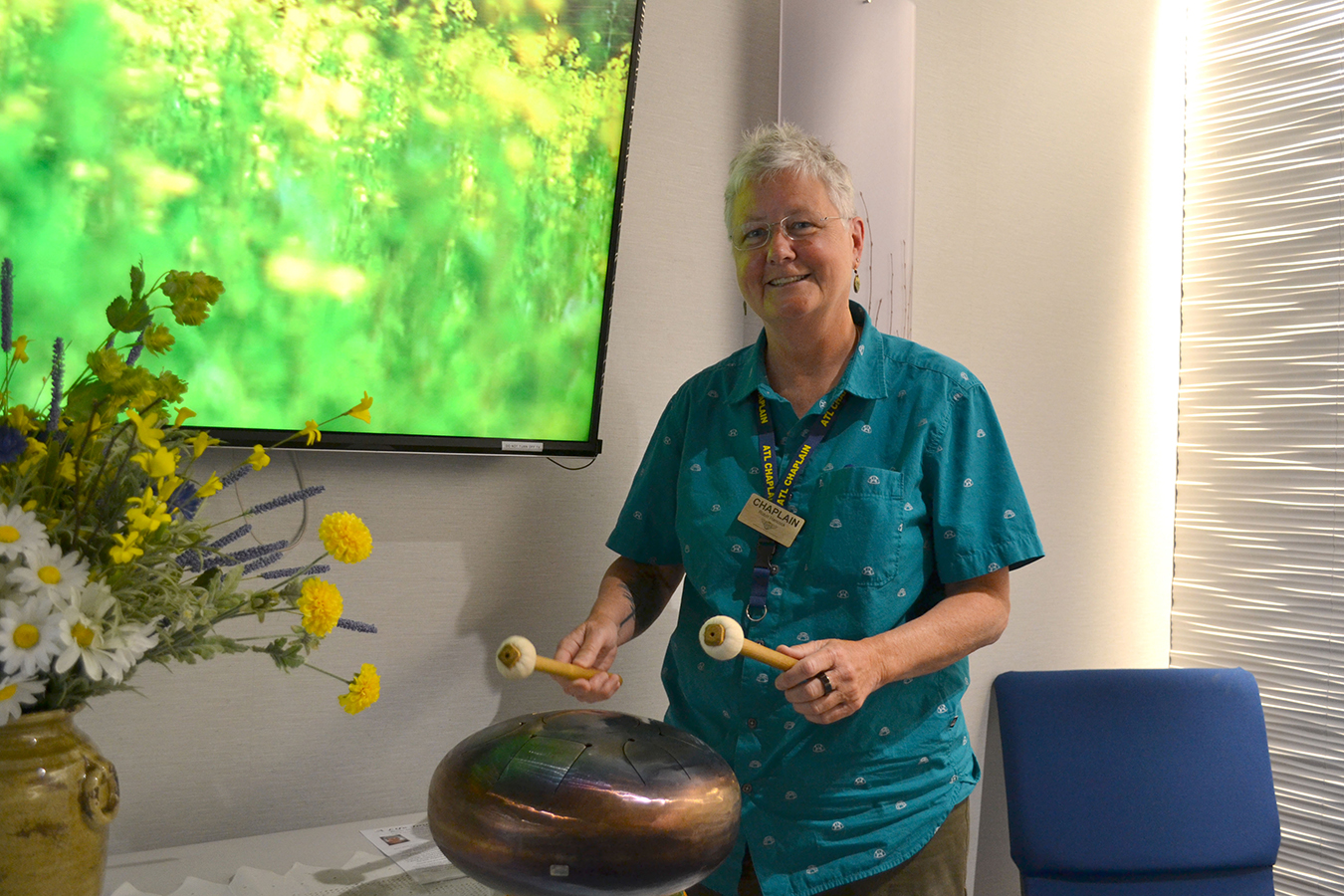

ATLANTA—Robin Hancock gently played her steel tongue drum with a pair of mallets, producing a set of soothing, mystical tones. They blended with the soft sound of chirping birds and bubbling creeks pouring from a Bluetooth speaker. Her warm voice invited the two visitors in the dimly lit room to slip into a nature setting of their choosing.

The 20-minute guided meditation took place at an unlikely location: Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, which until 2020 was the world’s busiest passenger hub. The airport interfaith chapel’s executive director, Blair Walker, introduced the meditation sessions last fall in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

People were noticeably more stressed during the past year, Walker said as he stepped out of his office onto the second-floor gallery, which overlooks the airport’s main atrium. Walker is an ordained minister who previously worked in higher education and public health. He said people have been quicker to lose their temper, lose their patience, or lose it altogether.

“There was a tightness that I’ve never seen before,” he said.

That’s why he brought Hancock, a nature meditation guide, on board to join his team of 40 volunteer airport chaplains. Hancock said her goal is to provide people with “a piece of calm in whatever storm is going on at that moment” and leave them with a tool to use the next time they’re feeling overwhelmed.

“Traveling is tough,” said Jordan Cattie, a clinical psychologist and assistant professor at Atlanta’s Emory University School of Medicine. Airports, in particular, trigger panic and anxiety because of the frenetic pace, noise, and glaring screens, she said. COVID amplifies travel anxiety.

Airport chaplains have become close witnesses to people’s worsening mental condition.

“No doubt, the pandemic has accelerated the need for our services to a new level,” said the Rev. Greg McBrayer.

McBrayer, an Anglican priest, is the corporate chaplain for American Airlines and director of the interfaith chapel at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, the world’s largest airport chapel. During the pandemic, he said he has seen depression, anxiety, and addiction increase among the travelers and workers served by him and his staff of 20 chaplains.

“We have encountered a tremendous amount of grief and fear,” McBrayer said, especially among airport employees. In the past year, he logged over 300 counseling sessions via Zoom and more in person.

Many struggled with economic woes, health concerns, COVID deaths, as well as with feelings of guilt for being well and employed when some of their former colleagues weren’t.

“We’ve seen a lot of workers come up to the chapel because they need a quiet space to sit, chill, and maybe cry,” said Walker.

In the early months of the pandemic, Hartsfield-Jackson also became a refuge for up to 300 homeless people per night, many with mental health conditions such as addiction and schizophrenia. They were redirected to hotels rented by the city. Now, the Transportation Research Board is conducting a $400,000 study of homelessness at airports, including how to stage mental health interventions.

“We will put together best practices of what airports can do to assist these vulnerable populations,” said Steve Mayers, the airport’s director of customer experience.

Chaplains typically encounter people in distress as they walk the concourses in what they call “the ministry of presence.” Walker and McBrayer said they’ve seen more breakdowns and panic attacks during the pandemic. Many of these events are triggered by the contentious issue of wearing masks, said Walker. A few weeks ago, a gate agent called when a passenger furiously refused to wear a face covering and then broke down as the airline took her off the flight.

“It was obvious there was much more going on than just the mask issue,” Walker said.

The guided mediation at Hartsfield-Jackson is designed to “help people breathe, recenter, step away,” said Hancock, who inherited a love of flying from her pilot father and volunteers at the airport once a week. On a busy day, each session has up to five participants to accommodate physical-distancing guidelines.

“I can read people pretty well,” she said. “Many of them carry a lot of vulnerability and angst right now.”

Most people are quiet when they come in, and their bodies are tense. Hancock remembers an older couple who were on their way to Texas for a family emergency. After the meditation, the couple became more talkative.

“They were fearful about what to expect. They were fearful about traveling,” Hancock said. “They were fearful just being among people.”

Cattie, the clinical psychologist, said practices such as mindfulness, meditation, yoga, and controlled breathing can be very effective at thwarting anxiety triggers that are inherent in air travel.

Mental health and well-being were on the radar of airport administrators long before COVID, but some services were paused because of the pandemic. Now, though, they’re making a comeback. Several airports have yoga, stretching, and silent meditation areas. Live music and therapy pet programs are also intended to calm stressed-out travelers.

As more people get vaccinated, passenger volumes continue to rise and more trips are for vacations and other joyous occasions. Still, Cattie expects the pandemic’s mental health fallout to last a while longer.

“COVID has seeped into every crack and every foundation and created so much loss and change and fear,” she said. “There will be a huge echo.”

In her clinical practice, she’s seen many patients who are anxious about rejoining life, with its crowded places and people on the move.

“This past year, many of us have been living in a safety bubble,” she said. For most people, traveling is a social muscle that hasn’t been exercised in a while. “It’s OK to be scared,” she said. “It’s normal to feel uncomfortable.”

Katja Ridderbusch is an Atlanta-based independent journalist. Print, radio, online. German-American. Ridderbusch focuses on health care, business, and social issues. This article was originally published on Kaiser Health News.

Be the first to comment