The pietà is a common theme throughout the history of Western art; it pertains to a work of art that depicts the Virgin Mary with her son Jesus Christ after Jesus’s death and descent from the cross. Depicting the mother’s love for her son after he endures great suffering, the word “pietà” roughly translates to “pity” or “compassion.”

Michelangelo’s Pietà

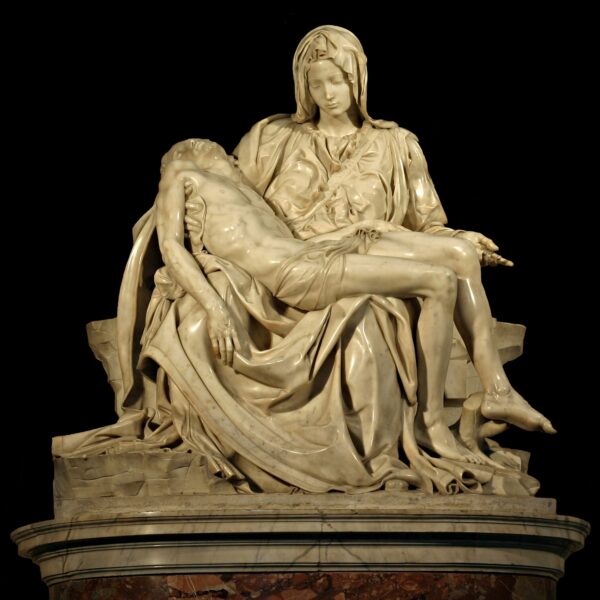

One of the most famous pietàs is by the renaissance artist Michelangelo. At the end of the 15th century, at the age of 24, Michelangelo finished “The Pietà,” commissioned by a cardinal named Jean de Billheres for a chapel at Old St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

Michelangelo said he created “The Pietà” from a perfect block of Carrara marble that allowed him to achieve a high degree of detail and polish. The finished product looked less like marble and more like clothed human beings.

He depicts the Virgin Mary saddened by the death of her son, whom she now holds in her lap. She has compassion for her son’s suffering but accepts his fate. The slightly raised brow reveals a very subtle hint of sadness upon the youthful Mary’s face.

Michelangelo was criticized for depicting the Virgin Mary so young. She’s shown to be around the same age as her son who now occupies her lap. Michelangelo’s response to this criticism was that women who remain chaste retain their youth and beauty.

The Virgin Mary is also depicted very large in comparison to Jesus. Michelangelo most likely did this to provide a surface for Jesus’s body; her body needs to appear larger if it is going to be able to hold and support the body of Jesus. The two together, however, are composed according to a triangle, a typical shape by which Renaissance art was composed.

“The Pietà” was the only work of art to which Michelangelo signed his name. As the story goes, Michelangelo overheard viewers attributing the work to another artist when it was first unveiled. In response to this, Michelangelo locked himself with the sculpture one night and signed his name on the sash draped across the Virgin Mary’s chest.

At first glance, the words on the sash read, “Michelangelo Buonarroti, Florentine, made this.” But according to Carl Smith, in his book “What’s in a Name? Michelangelo and the Art of Signature,” the signature is combined with strange dots and symbols that all together may mean “The Florentine Michelangelo Buonarroti, a messenger from God, made this.”

Anthony van Dyck’s Pietà

After the Renaissance and by the time of the 17th century Baroque, Anthony van Dyck was composing his own Pietà. Instead of just depicting Virgin Mary and Jesus like Michelangelo, van Dyck includes Mary Magdalene and Saint John.

Jesus’s body is shown draped in white and lifelessly reclines against a rock and the Virgin Mary who sits behind him. Though Jesus is dead, his halo still shines from his head indicating that the divinity of his soul is well and alive.

The Virgin Mary is dressed in blue behind Jesus. Her eyes, red with tears, look sullenly to heaven. The pain on her face expresses the compassion she has for her son’s sufferings. The palm of her left hand is open, and she gestures as if presenting her son to heaven.

Dressed in red and gold, Mary Magdalene kneels to the right of the Virgin Mary and Jesus. She too has an expression of sadness. She takes Jesus’s hand in hers and kisses it. Saint John leans into the picture frame from the far right and contemplates the scene.

At the bottom left are the crown of thorns, the paper that was nailed at the top of the cross which read “Jesus of Nazareth, King of Jews,” and a basin and sponge with which the Virgin Mary cleaned her son’s body.

Van Dyck has increased the drama of the composition in ways typical of Baroque art. He’s forgone the static and calm triangular composition of the Renaissance artists in favor of more curves, movement, and emotion in an attempt to more fully relay the drama of the event.

William Bouguereau’s Pietà

Almost 250 years later, William Bouguereau, foremost representative of the French Academic style of painting, painted his own version of the Pietà, partly inspired by the death of his eldest son.

In the center of the composition is the Virgin Mary, dressed in black to mourn the death of her son. She firmly holds her son’s lifeless body in her arms and stares out toward the viewer with a pained expression. The two figures possess gilded halos which represent their divinity.

At the bottom right of the composition, we again see the crown of thorns and the basin of water and sponge with which Jesus’s body was purified.

Framing the two central figures are nine angels mourning the scene with different expressions and body language. The nine angels wear the colors of the rainbow, which reiterates God’s promise to renew the world after Noah’s flood in Judaic traditions; here, it again represents renewal, but of the human soul after the sacrifice of Jesus in Christian traditions.

Interestingly enough, Bouguereau put the personal pain of losing his own son into the expression of the Virgin Mary. Depressed for six months after losing his son, this painting became a way for Bouguereau to renew his own spirit.

With this in mind, the colors of the angels’ robes in combination with the black and white worn by the Virgin Mary and Jesus may also represent the full palette of paint by which the artist made his creations. In other words, all of the figures in this painting are possible representations of the idea that the divine is responsible for both the renewal of one’s spirit and artistic creation.

Three Different Approaches to a Relatable Story

We’ve come to see three different approaches in depicting the love a mother has for her suffering son. Michelangelo idealized the Virgin Mary and Jesus into a calm and accepting scene of suffering. Van Dyck dramatized the scene in an attempt to touch emotionally as many viewers as possible. Bouguereau created a powerful image by using his own personal painful experience as inspiration.

The one thing that is consistent across all of these approaches, however, is the depiction of compassion itself. We may not all have kids, but most of us have someone in our lives that we care deeply about, or maybe we care deeply about humanity as a whole. Everyone suffers, irrespective of socioeconomic class, race, gender, and so on. These images serve, at least in part, as encouragement to be compassionate toward those who suffer.

Eric Bess is a practicing representational artist and is a doctoral candidate at the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts (IDSVA).

Be the first to comment