I was first introduced to Dan Eastland of Dogwood Custom Knives while roaming the aisles of a popular outdoor trade show in Atlanta, Georgia.

Dan Eastland has qualifications that would make most hardened outdoorsmen look like greenhorns. From his firefighting background to his engineering, woodworking, landscaping and military experience, he knows what works. He is a guy who uses the tools he makes, which is a huge plus in my book.

Upon visiting his booth, I was also struck by the simple, effective-looking designs and the stellar leatherwork sheathes made by Matt Gilenwater. Each of Dan’s knives fit snugly into the sheath and deployed smoothly and predictably. Matt manufactures all the leatherwork for Dogwood. In addition, he produces his own line of custom sheaths and “possibles bags.”

After a few encounters with Dan, I knew I wanted to try out his masterpieces and familiarize myself with his lineup. Once we decided on the knives, it was time to use them in my primitive bush camp in the Northeast.

Dogwood Tools

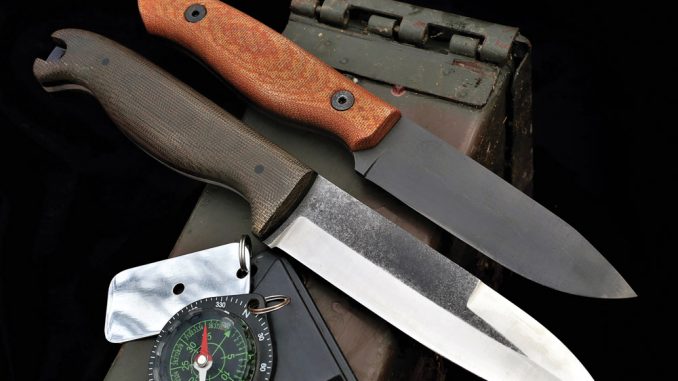

I tested two knives for this article: the Echo-7 and the Combat Kephart. The Echo-7 has an overall length of 8½ inches and has a 4-inch blade. It features Micarta scales that are textured yet still hand-friendly. Thickness is about 1/8 inch with a flat grind and micro bevel. The blade features a black coating to help protect the O1 tool steel. This piece is based on the Echo-5 model that Dogwood offers, which is the workhorse of its custom line.

ONCE I GOT BOTH KNIVES INTO MY WINTER CAMP, I NEVER HIKED THEM OUT UNTIL SPRING. I CACHED THEM IN A LOG OR UNDER A PILE OF FIREWOOD DURING THE RAIN AND SNOW. SOMETIMES, THEY WERE KEPT IN THEIR SHEATHS, AND SOMETIMES, I PUT THEM IN A PLASTIC BAG.

Both the Echo-7 (orange) and Combat Kephart (brown) have slightly contoured Micarta scales. All the contours are rounded to eliminate any hot spots.

The Combat Kephart has a blade made of CPM-154 with an antique finish that gives it a bit of style and helps kill any unwanted reflection. This one is 9¾ inches overall, with a 5-inch blade. The Kephart-style blade is a go-to knife for the kind of field work many soldiers do. By adding a false edge to the top, it becomes a great blade for the one-in-a-million chance that it is needed for hand-to-hand combat. However, there are many other uses for a false edge in wilderness camping.

Each knife is clothed with a beautiful leather belt sheath.

Proving Grounds

Winter is the best time of the year to test outdoor gear in the wilderness, especially knives. In a “winter” camp, there are extra imperatives for having a fire going constantly: warmth; and, if camping, the fire will be needed as a light source during the long winter nights. A comfortable, sharp knife is paramount for this to be done efficiently. A thin-beveled blade, complemented by a comfortable handle, will do more work in a camp all day long than will a thick-beveled knife meant only for heavy work.

Dan Eastland only makes comfortable, rounded scales for his knives. The author has never experienced any hot spots or discomfort during testing—which includes a total of six knives so far.

The exposed pommel often found on Dogwood Knives makes for a less-than-lethal weapon or glass breaker.

Dan makes knives that cut, slice and carve with all the comfort needed for regular use in conjunction with a heavier tool meant for chopping and splitting. A combo such as this is a godsend for most wilderness outings. So, most of my testing was done in tandem with a bow saw or tomahawk.

The Echo-7 (top) and Combat Kephart (bottom) are two very different “animals” from Dogwood Custom Knives. Both are comfortable, full of utility and don’t shirk when there’s work to be done.

The Echo-7 was used first for my early-winter outings, because it was the lighter of the two. It readily handled fire preparation and basic carving of utensils needed to cook some tilapia over an open flame. For this, I selected a piece of wood about broomstick thick as my main cooking pole. Green wood is ideal, because it won’t burn; however, dry hardwood is also acceptable if it is a hardwood such as maple, beech or hickory. As long as it is not rotten, it will work, because the wood is not over a direct flame. Rather, it is over hot coals or a very low flame.

The leather belt sheath you receive with a Dogwood knife is sure to fit snuggly and look handsome.

The knife was used to first make a split about 7 or 8 inches down the straightest part of the branch. Once the split was established, the ends could be cleaned up a bit by lightly carving the end to get any dirt and bacteria off that might come in contact with the food. Small, thin, green twigs a little thinner than a pencil are needed to impale the fish and keep it rigid while over the heat source. With a simple point on each end, it’s nothing fancy, but this is the fine work a thin bevel does well.

Two formidable blades from Dan Eastland at Dogwood Custom Knives, the Echo-7 (left) and Combat Kephart (right) are highly capable in the wilderness and for combat and survival duty.

Straight, green witch hazel was used to make a figure-4 deadfall trap. The Echo-7’s handle proved to be comfortable, and the blade was razor sharp. The knife performed all tasks well and was durable when cross-grain batoning into dry and green wood.

I often use a chest-lever grip for more control when sharpening thin sticks. The handle has a bit of a contour to it (which I am not a fan of), but the Echo-7 doesn’t have so large a belly on the front of the handle that it gets in the way of a chest-lever grip. It was comfortable and versatile, as all knife handles should be.

A THIN-BEVELED BLADE COMPLEMENTED BY A COMFORTABLE HANDLE WILL DO MORE WORK IN A CAMP ALL DAY LONG THAN A THICK-BEVELED KNIFE MEANT ONLY FOR HEAVY WORK.

I went on to make a figure-4 deadfall trap with the knife to see how comfortable it really was. I strongly believe that if you want to see how hand-friendly a knife is for long-term use, make something!

A figure-4 trap, although simple, has a few cuts that are repeated and need to be set in the proper place for maximum efficiency. This trap requires both fine, detailed work carving clean notches, as well as some medium-hard work when it comes to cross-grain batoning into thick green wood or dry hardwood.

A simple fish-roasting pole was made with the Echo-7 by splitting the stick, shaving down the wood contacting the fish and sharpening a couple of skewers to hold the fish inside the pole.

This is done by placing the knife blade where the stop cut (straight edge) needs to be and giving the blade spine a few whacks to penetrate deep enough to create a straight notch where the carving will end. Then, the shavings are cleanly released. This type of cross-grain baton work is a regular part of many woodcraft chores, such as sectioning wood down to size and making notches on green and dry wood.

DAN’S EDGES WERE JUST FINE FOR THESE SORTS OF TASKS. AND, REGARDLESS OF THE AMOUNT OF CARVING AND BATONING, LOSS OF SHARPNESS OR EDGE DEGRADATION WAS NEVER AN ISSUE.

The Echo-7 was used to split the stick to fit the fish to the pole.

Dan’s edges were just fine for these sorts of tasks. And, regardless of the amount of carving and batoning, loss of sharpness or edge degradation was never an issue.

I treated the Combat Kephart as a “solo survival knife,” relying on it for many forms of survival without the aid of a saw or chopper. Naturally, I started out with fire preparation, one-stick-fire style. I selected some hardwood maple and softer poplar wood for my winter fire. The maple log was split with the help of a wooden maul I fashioned. I split the log until I had pieces that were thick enough for fuel and pieces thin enough to be used as pencil- and finger-thick kindling.

The author made a survival spear for roasting meat, as well for use as a quick, field-expedient weapon for camp protection.

The false edge on the front of the spine gets a bad reputation and is often criticized for not being a good surface on which to use a baton, mainly because it eats up the baton/beater stick and doesn’t allow enough effective energy transfer. In reality, if that’s the blade design you prefer, who cares? Just grab another stout stick and continue working, despite how it might shred your baton.

The softer poplar wood was split and used as my tinder. It made fine, thin shavings that would be used to catch a spark from a ferrocerium rod.

The Combat Kephart has a natural place to strike a ferrocerium rod on the false edge (spine). When stabbed into a stump with a fuzz stick underneath it, it took only a few swipes to ignite the poplar wood shavings.

This is where the thin edge geometry shines on Dogwood knives. The shavings need to be curly and densely grouped to catch a spark easily. When it comes time to make the ignition, the false edge was used as a striker by stabbing the knife into a stable log and placing the fuzz stick against the false edge. A ferrocerium rod was used to scrape against the false edge, creating a shower of hot sparks onto the thin wood shavings. From there, it was just a matter of transferring the tinder to the main fire lay for a good camp fire.

Using a heavy maul (right) on the false edge portion of the Combat Kephart to split wood was not as hard on the maul as many would think. In any survival situation, it wouldn’t matter how chewed up the maul got.

I made a four-prong gigging spear that could be used for camp security, frog or fish gigging, or as a caveman-style meat roaster—which is my preferred way to use it. Again, green wood is ideal, but it is always good to use what nature provides with the minimum amount of work required.

I located a downed tree from the winds we had in late autumn and used a baton stick to beaver-chew through a long pole that was about wrist thick. Once I cut it free, I cleaned up the cut end so it would be smooth enough to handle without gloves. I found the straightest end to baton into four sections with two perpendicular cuts about 8 inches down the length, also with the aid of a baton stick.

The author made a one-stick fire using only the Combat Kephart and baton. All the splitting and fuzz sticks, as well as various-sized kindling sticks, were processed with this knife.

Once I had my four prongs, I sharpened them first as one unit while securely holding the ends together and then individually for fine-tuning. The Combat Kephart was just the right size—not too large or too awkward to do serious work.

Wear and Tear

Once I got both knives into my winter camp, I never hiked them out until spring. I cached them in a log or under a pile of firewood during the rain and snow. Sometimes, they were kept in their sheaths, and sometimes, I put them in a plastic bag. The coating on the Echo-7 kept the blade rust free. The inherent properties of CPM-54 kept the Combat Kephart from rusting. The edges were never retouched, because they never got dull. The leather sheaths remained rigid and tough—while looking classy all the way.

Fine sharpening in a chest-lever grip was easy and comfortable with the Echo-7. Even out near the tip, at the belly of the knife, control was never an issue, because the sharp, thin blade shaved wood effortlessly.

If you are looking for knives that can be used with ease and comfort, check out Dogwood Custom Knives. Dan takes custom orders and is a guy who stands by his work.

… IF YOU WANT TO SEE HOW HAND-FRIENDLY A KNIFE IS FOR LONG TERM USE, MAKE SOMETHING!

Splitting scrap wood to help feed a winter fire was done with the Combat Kephart. Altogether, it built about 10 fires in the early winter months.

I asked him about his goal and mission when it comes to Dogwood, and he said, “If, one day, a grandfather hands his grandson one of my knives and says, ‘My dad gave me this knife when I was your age,’ then I will consider myself a success.”

I think Dan has already achieved this!

Fire Fly Handle Scales

Dan told me that he has crawled around in debris looking for his knife, hoping to find the handle—before the blade. From his desire to reduce this nuisance for others, he developed what he calls Fire Fly, and it is definitely a game-changer. Fire Fly is a proprietary material that provides eight to 10 hours of glowing light after just 30 minutes of exposure to direct sunlight. The bright-colored resin makes it highly visible in dim or dark environments.

Dan said that having chunks suspended in the handle scales increases the surface area of the glow material, making the knife easier to find. Also, light passing through the translucent material gives a greater perceived glow. Fire Fly is very resistant to the elements, making it suitable for everyday-use items. Small pieces that have been drilled out are being tested as hammock attachments to help campers see the lines in the dark or as zipper pulls for a backpack or pouch. Dan mentioned that they would also make handy trail markers.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared in the March, 2018 print issue of American Survival Guide.

Be the first to comment