In the rich tapestry of Western civilization, certain themes and stories keep recurring. They mark our culture’s continuity as each generation finds new meaning in them.

From the Middle Ages to the present, the legend of Faust has never gone away. It speaks to people in every time and place. Why? Perhaps because each of us faces the same choice: to live for worldly rewards like money, pleasure, or fame, or to dedicate ourselves to higher, more selfless goals.

The Faust story, echoing Christ’s temptation in the desert and the ancient cautionary tales of Prometheus and Icarus, symbolizes this eternal human struggle.

There actually was a Doctor Faust, a 16th-century German astrologer whose dabbling in magic got him banished from towns and accused of selling his soul to the devil. Over the years, so many legends grew up around his name that it’s impossible now to separate fact from fiction. His story became one of the fundamental myths of the West.

Two Masterpieces

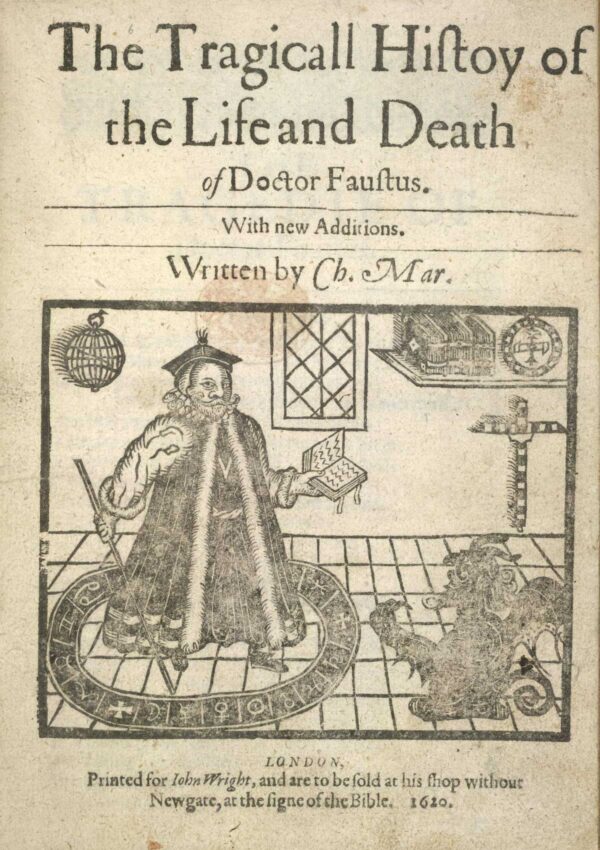

In 1587, an anonymous “Faust Book” was published in Frankfurt Am Main, supposedly stories from the doctor’s life but mainly rumors and folk tales. Somehow this got into the hands of Christopher Marlowe, a brilliant young playwright born the same year as Shakespeare, who turned the stories into his masterpiece “The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus.” Marlowe was an enigma: He was accused of being a spy, a ruffian, and an atheist before dying in a knife fight at age 29.

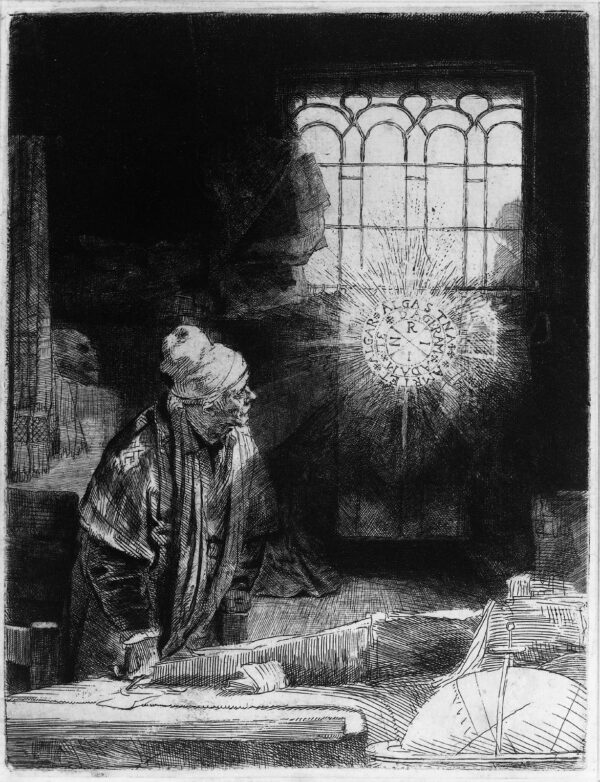

Marlowe’s is the first known dramatization of the story. His Faustus embodies the Renaissance quest for knowledge through science, but the character’s curiosity and pride push him further— down the slippery slope of witchcraft. Taking a cue from medieval mystery plays, Marlowe gives Faustus two angels, one good and one evil, to advise him. Egged on by the bad angel, Faust signs a blood pact with the demon Mephistopheles, gaining supernatural powers for 24 years at the cost of spending the rest of eternity in hell.

For years Faustus fritters away his powers, amusing aristocrats with conjuring tricks and raising the gorgeous Helen of Troy from the dead to be his lover. Marlowe gives his damned hero some of the most beautiful lines in English poetry:

Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships,

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss!

Her lips suck forth my soul—see where it flies!

Come, Helen, come, give me my soul again!

Here will I dwell, for heaven is in these lips.

But heaven and immortality are not to be found in Helen’s sweet caresses. Time runs out for Faustus. He tries to repent, but it’s too late. Mephistopheles and his demon buddies drag him away to hell. Marlowe denies his Faustus any hope of forgiveness or redemption.

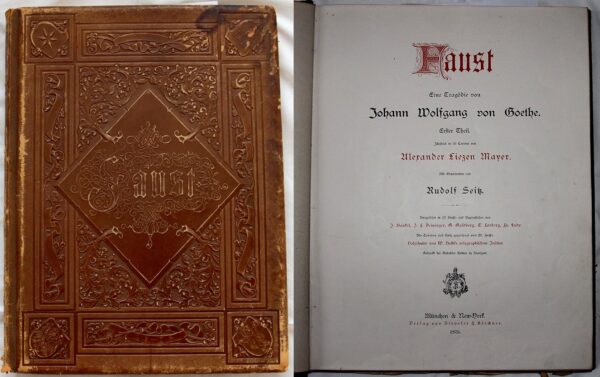

In 1808, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published his own “Faust, Part One,” a poetic drama that many consider the crown jewel of German literature. Goethe adds a crucial new subplot: Faust’s pursuit of Gretchen, an innocent village girl he seduces and abandons.

This version begins, like the Book of Job does, with Satan betting God that he can lead his faithful servant astray. Goethe’s Mephistopheles tempts Faust by giving him worldly wealth and power, unlike Job, whom Satan tempts by taking them away.

As Goethe completed his “Faust” (“Part Two” appeared in 1832), he changed his mind about Faust and Gretchen’s ultimate fates. Both are damned in an early draft, but in Part Two, Faust is rescued by, of all people, the girl he victimized. Pregnant and alone, shunned by the people of her village, Gretchen desperately drowns her newborn. When Faust learns of her arrest for murder, he tries to magically spring her from prison, but she refuses, accepting the punishment for her sin.

But that’s not the end. God, seeing Gretchen’s initial innocence and contrition, saves her soul and she, in turn, intercedes on behalf of Faust. Like Dante’s Beatrice, she leads him, now redeemed by God’s mercy, to paradise.

Quite a change from Marlowe, where the wages of sin are death, period. For Goethe, as for Dante, romantic love points us in the direction of God’s love, but must be transcended finally to get there.

After Goethe, authors as disparate as Louisa May Alcott (“A Modern Mephistopheles”), Oscar Wilde (“The Picture of Dorian Gray”), and Thomas Mann (“Doctor Faustus”) produced their own variations while Stephen Vincent Benét’s story “The Devil and Daniel Webster,” memorably filmed in 1941, transported the story to America.

Face the Music

As the 19th century progressed, Faust learned to sing. Goethe’s poem inspired composers all across Europe. Franz Schubert’s 1814 song “Gretchen am Spinnrade” (“Gretchen at Her Spinning Wheel”) is famous, but Beethoven wrote a Faust song even earlier.

Richard Wagner’s turbulent “Faust Overture” (1840) was one-upped by his father-in-law, Franz Liszt, whose marvelous “Faust Symphony” (1854) has three movements, one for each of the main characters: Faust, Gretchen, and Mephistopheles.

The opera world really went crazy for Faust. About 20 Faust-inspired operas have appeared to date. The best-known are Charles Gounod’s “Faust” (1859), for decades the world’s most popular opera, and Arrigo Boito’s “Mefistofele” (1868). Hector Berlioz’s “La Damnation de Faust” was poorly received on its debut in 1846, but the reputation of this hybrid opera-oratorio has risen since.

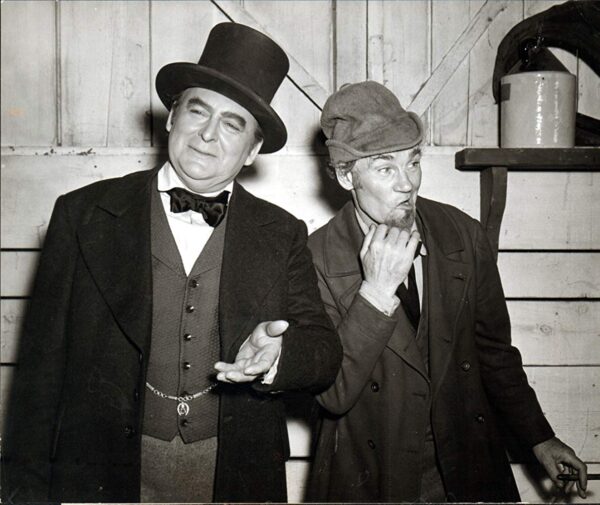

Faust inspired the classic American musical “Damn Yankees,” where a middle-aged baseball fan sells his soul to the devil to be transformed into a major league slugger. A sultry female demon lures him to the dark side with the hit song “Whatever Lola Wants, Lola Gets.” But rest assured, the devil (played on Broadway and in film by Ray Walston of “My Favorite Martian” fame) is foiled in the end.

In the Movies

The Faust story’s visual potential made it a natural for the 20th century’s new art form, motion pictures. As early as 1900, Thomas Edison’s company released “Faust and Marguerite,” a vignette only 57 seconds long! In France, in 1904, Georges Méliès (“A Trip to the Moon”) made his own 15-minute “Faust and Marguerite.” It was his fourth crack at the story—the first was in 1897.

The definitive cinematic Faust appeared in 1926. Germany’s biggest film studio, UFA, decided to celebrate its 10-year anniversary by letting its two leading directors make spectacular, no-expense-spared epics. Fritz Lang made “Metropolis” and F.W. Murnau made “Faust.”

Murnau’s “Faust” isn’t as well-known today as his earlier, iconic “Nosferatu.” Contemporary critics found it too slow and too stylized, but some called it the most beautiful film ever made. Seen for decades only in blurry dupes, the film was finally restored to its former glory in 2015.

Throughout the 20th century, Faust adaptations came thick and fast. New movie versions, more or less faithful, issued from France, Russia, Spain, Italy, Germany—even, in 2019, from South Korea.

Updatings like “Bedazzled” (1967, remade in 2000) and “Phantom of the Paradise” (1974) found comedy in the story. Faust references kept popping up in poetry, prose, and popular music. Animated films, TV shows, graphic novels, comics, and a seminal Japanese manga retold the story for new generations.

Faust even entered the language. Trading one’s moral integrity for short-term gain is a “Faustian bargain.” Oswald Spengler used “Faustian man” and “Faustian culture” to describe a West he felt was selling its soul to technology in return for unlimited knowledge. And “Mephistophelean” is defined as “showing the cunning, ingenuity, or wickedness typical of a devil.”

It’s been said that we are all Hamlet. We are all Faust, too, constantly tempted to violate our higher principles for the immediate gratification of approval, success, and all the other glittering prizes the world has to offer. Goethe’s Faust had Gretchen to put in a good word for him in heaven. We may not be so lucky, so it’s up to us, every day, to make the right choice.

Stephen Oles has worked as an inner city school teacher, a writer, actor, singer, and a playwright. His plays have been performed in London, Seattle, Los Angeles, and Long Beach, California. He lives in Seattle and is currently working on his second novel.

Be the first to comment