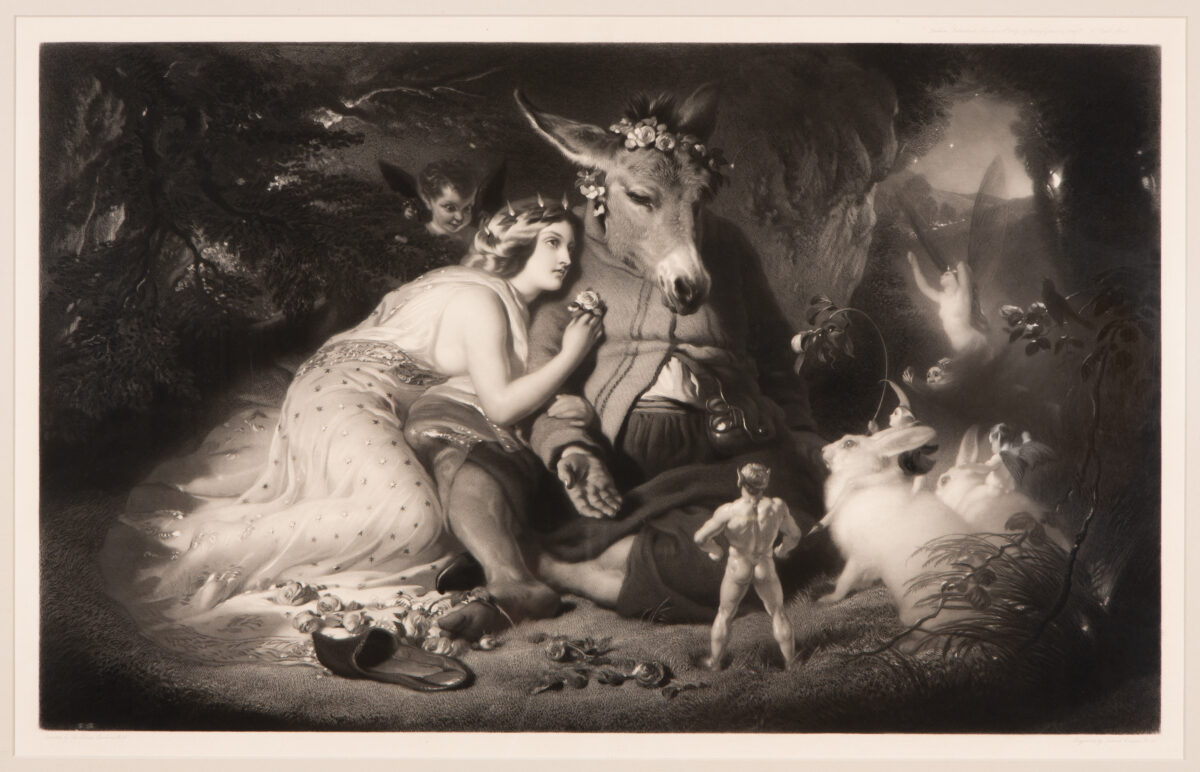

Two works of art in the same medium can often be connected like pearls on a string, one leading to the creation of another, and then another. However, just as often, several works of art in different media can be interconnected in something more like a three-dimensional nexus. That can be fascinating to explore from any direction, whether starting with music, drama, dance, or even culture generally. I came across such a labyrinth recently when revisiting “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” in its various incarnations.

The question had arisen in casual conversation about the changing seasons, in regard to a cold spell that came through and threatened our newly planted garden. “When will summer finally begin?” I asked my wife in frustration. “And, by the way, when is ‘midsummer’? You know, like in Shakespeare? And why did he choose that as a title?”

To that, always a step ahead of me, she characteristically non-replied, “O, put on the Mendelssohn!” Composer Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) had written both a precocious overture to Shakespeare’s play in 1826 (Opus 21), when he was only 17, and then incidental music for the play 16 years later, which incorporated the earlier overture at the beginning (Opus 61).

I discovered that there is, in fact, a particular day called “midsummer,” traditionally June 24, in celebration of the summer solstice, a holiday that predates Christianity. (In some years, the solstice can vary slightly from that date.)

In northern countries, there is also an ancient note of magic about the day. In Sweden, it is a huge national holiday, with special foods and dancing around a pole. In Britain, there is dancing and drumming at the site of Stonehenge. It is a day when Shakespeare’s fairies and other magical creatures might indeed be expected to play a dreamlike role, hence his title.

Music and a Play Become a Ballet and a Wedding Tradition

Shakespeare’s story and Mendelssohn’s music found a natural intersection in dance. It so happens that the very first, original, full-length ballet choreographed by George Balanchine (1904–1983) was given its premiere by the New York City Ballet on Jan. 17, 1962, to Mendelssohn’s music and Shakespeare’s story.

Although Balanchine is widely known as a father of contemporary ballet, this work is choreographed quite elegantly and beautifully in the relatively traditional neoclassical style. Neoclassical ballet, invoking the simplicity of an ancient Greek look, retains the beautiful traditional music and the moves of Romantic ballet but sheds the grandiose sets and costumes in favor of clearer visuals so that one can really see the dancers’ arms and legs in motion. Balanchine’s version of the Mendelssohn remains a classic.

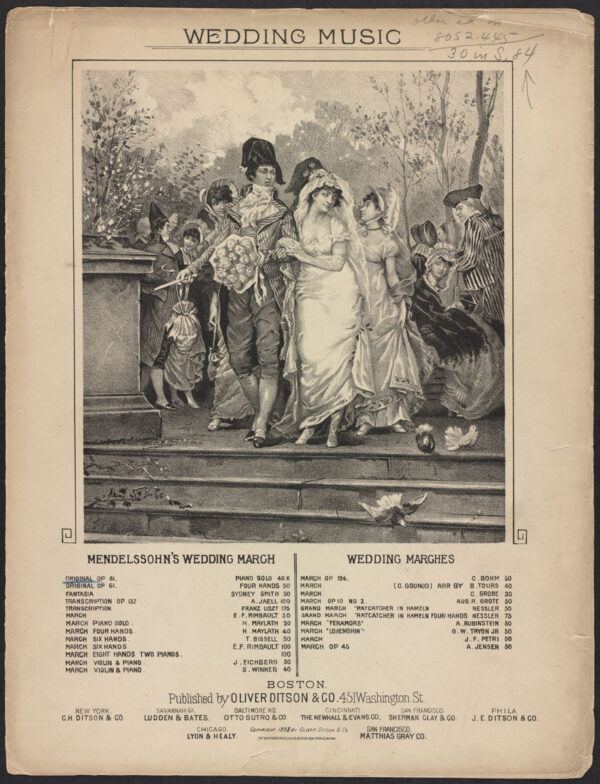

Another notable feature of Mendelssohn’s 1842 suite of incidental music for the play was his addition of his famous “Wedding March,” which has since been used for the bride’s entry procession at countless weddings, perhaps even for the weddings of many people reading this. How did that come about?

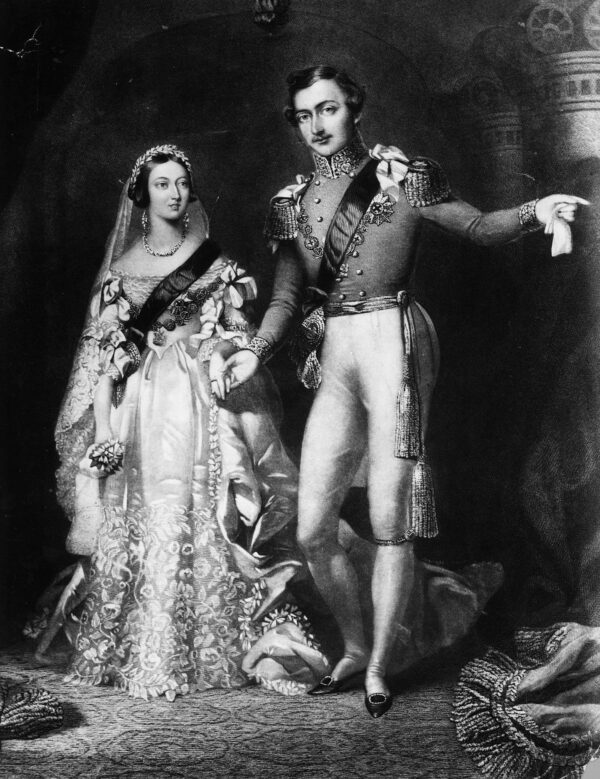

It seems that Queen Victoria originated several traditions that were borrowed by the people of England and eventually made their way to the United States and other countries. For example, she and her husband, Prince Albert, began putting up a Christmas tree inside their palace, a practice that he had grown up with in Germany but which was not the custom in England. Soon enough, most people in England had a tree at Christmas, and thus so do we.

Before Queen Victoria’s wedding, bridal gowns were not typically white—you guessed it—until she was married in a white gown. But in this case, it was her eldest daughter, Princess Victoria Mary Louise, who influenced the wedding customs. She was a fan of Mendelssohn’s music and set the example of using his “Wedding March” at her 1858 wedding to Prince William of Prussia.

That music was known to have been used at a wedding just once before, by Dorothy Carew and Tom Daniel in Tiverton, England, in 1847, but it was not until the princess used it that it came into vogue. In fact, having a procession up and down the aisle itself was an innovation at her wedding.

Tradition Lives On, But Barely

From this line of inquiry, and having not been to a wedding lately, I naturally wondered whether people are still marrying in June and still using the wedding march. It appears that the midsummer month of June (whether due to Shakespeare or to the weather) is still the most popular month of the year in which to marry, with, according to The Inspired Bride blog, 10.8 percent of all weddings taking place that month, but it is closely followed by August, May, and July.

Mendelssohn’s wedding piece, and also Richard Wagner’s wedding march (popularly known as “Here Comes the Bride”) from his opera “Lohengrin” can still be heard at a few weddings, but some religious traditions have shunned them both, due to the pagan weddings in the Shakespeare play or the ultimately tragic fate of the couple in Wagner’s opera. Also, many couples are getting married in parks and other outdoor venues, where there are no organs or ensembles to produce the big sound ideal for those traditional wedding pieces.

Instead, one hears all sorts of popular songs. Searching for the “top wedding songs” online produces no consensus whatsoever, but a whole range of popular hits, from Etta James, to Elvis, to Shania Twain, to Adele.

But as it turns out, according to Pew Research, only about half of couples marry at all now; the other half choose cohabitation.2 However, we like to think that traditions in decline, be they musical or marriage itself, can return and flourish once more with a new generation.

In any case, I have now traveled through this network of connections and hope to return again, full circle, to Shakespeare’s play, but to return even more often to the charming flutter of fairy wings produced by the violins after the opening five chords that begin both versions of Mendelssohn’s music for the play.

American composer Michael Kurek is the composer of the Billboard No. 1 classical album “The Sea Knows.” The winner of numerous composition awards, including the prestigious Academy Award in Music from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, he has served on the Nominations Committee of the Recording Academy for the classical Grammy Awards. He is a professor emeritus of composition at Vanderbilt University. For more information and music, visit MichaelKurek.com

Be the first to comment