I am a lover of essays.

Every morning, shortly after dawn, I sit at my laptop, coffee at hand, and explore the internet looking for pieces to read for enjoyment or as a kickoff for an article of my own.

On my bookshelves are scores of novels, once also a favorite genre, but over the years I have amassed equal numbers of volumes of essays, collections by such diverse writers as Joseph Epstein, Richard Mitchell, Alice Thomas Ellis, Hilaire Belloc, and Florence King. Here too are anthologies like Phillip Lopate’s “The Art of the Personal Essay” and Epstein’s “The Norton Book of Personal Essays.”

Nearly all these writers share some common characteristics. They often interject humor into their work—some of it biting, some gentle, some self-deprecatory. They point out hypocrisy, they praise sincerity, and they reference facts, historical figures and events, and literature while at the same time inserting themselves into their explorations.

This blend of personality and observation in nonfiction writing is a relatively new form of expression, a product of the French Renaissance, and generally credited as the invention of one man.

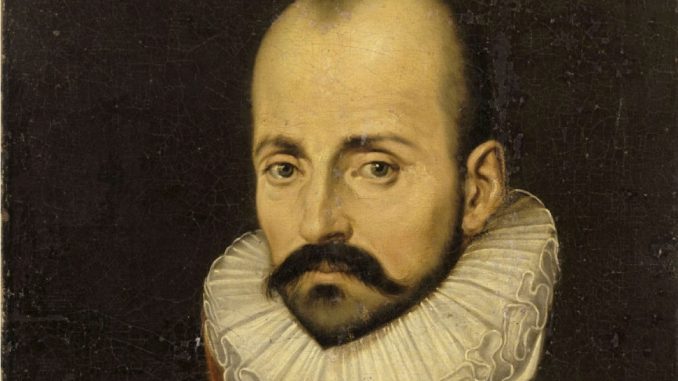

The Great Granddaddy of the Essay

Michel de Montaigne was born in 1533 near Bordeaux. His wealthy father, whom Montaigne once called “the best father that ever was,” oversaw his son’s education, instituting such unusual measures as having his son waken to music every morning and teaching him Latin before he learned French.

As an adult, Montaigne held several political offices. He also found himself caught up in the turmoil of France’s religious unrest. Several times he served as a diplomat, was admired by both Catholics and Protestants for his tact and his tolerant attitudes, and was twice elected mayor of Bordeaux. He married Françoise de la Cassaigne, a union that produced six children though only a daughter survived past infancy. He died in 1592 in the family home, Château de Montaigne.

And he wrote personal essays, thereby creating a new form of literary expression.

The Pioneer

The word “essais,” which Montaigne used to describe his generally short and subjective pieces of writing, comes from the French verb “essayer,” meaning “to test,” “to attempt,” “to exercise,” and “to experiment.”

This verb describes perfectly Montaigne’s writings. His essays are haphazardly arranged in his books, and the subjects range from friendship to cannibalism, from prognostications to smells, from the education of children to drunkenness. Like modern essayists, Montaigne puts himself in the middle of these pieces, happily making arguments and tossing off opinions, and marshaling other writers, many of them Greek and Roman, into his ruminations.

His casual style and discourse were innovative for his time. As he writes in a brief introduction in 1580: “I have dedicated it (the book) to the private convenience of my relatives and friends, so that when they have lost me (as soon they must), they may recover here some features of my habits and temperament, and by this means keep the knowledge they have had of me more complete and alive.”

In the next paragraph he adds: “I want to be seen here in my simple, natural, ordinary fashion, without straining or artifice; for it is myself I portray.”

An Amateur Looks at Montaigne

Montaigne and I are only recently acquainted.

Our budding friendship happened in this way. Several months ago, in some now forgotten online article, I stumbled across a favorable mention of Sarah Bakewell’s “How to Live, or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer.” After bringing the book home from the library, I ambled through “How to Live,” stopping here and there to read a certain passage, and then went in search of the essays themselves.

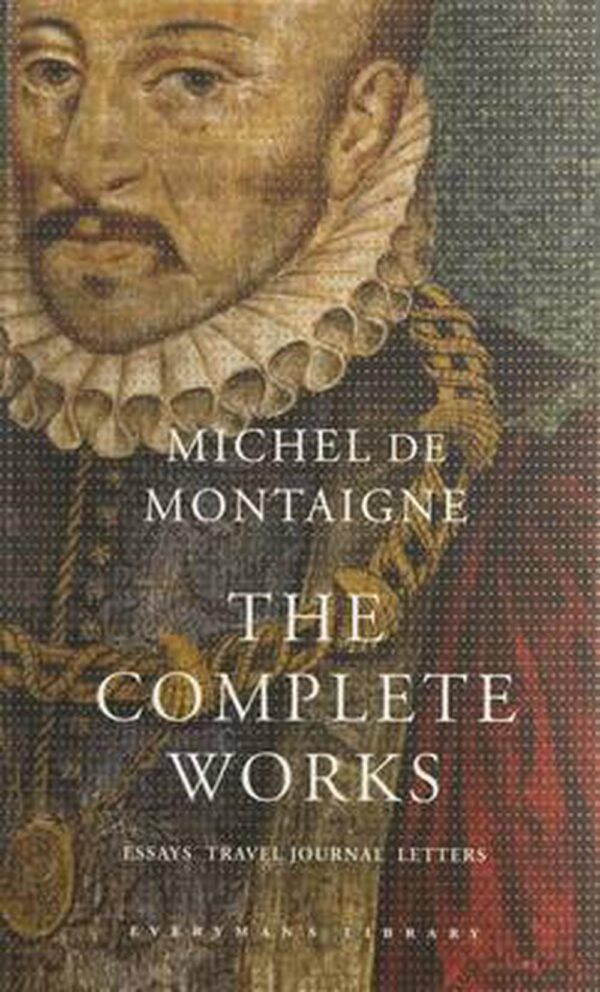

These I again found in the library: the Everyman’s Library edition of “The Complete Works.” It is a daunting compilation consisting of 1,336 pages translated by Donald Frame, who surely suffered from eyestrain and writer’s cramp by the time he completed his climb up “Mount Montaigne.”

Classical Influences

Montaigne, as I found in reading some of these essays, was a man of erudition. In addition to being well-educated and a lifelong reader to boot, he holed up in his château with a private library of 1,500 works when he first began writing these “attempts.”

To read Montaigne is to become aware not only of his extraordinary classical education, but also of his ability to remember passages from various texts and bring them into his writing. In his brief essay—it’s less than two pages—“On Idleness,” for example, he quotes Virgil, Horace, Martial, and Lucan. In “Of the Education of Children,” a much longer piece, Montaigne introduces several dozen classical writers to his readers, dropping their names as casually as a modern essayist might mention the names of Einstein, John Wayne, and Donald Trump.

Anyone who doubts the influence of the Greeks and Romans on the Renaissance has only to read Montaigne, who after all was writing not just for himself but also for “relatives and friends.” This audience would have recognized the philosophers, historians, and poets he mentions.

Contemporaries

In his “On Books,” which I read because of my own love affair with the printed word, Montaigne reassures his readers that contemporary literature has a place in our libraries and in our affections. He writes: “Among the books that are simply entertaining, I find, of the moderns, the ‘Decameron’ of Boccaccio, Rabelais, and ‘The Kisses’ of Johannes Secundus, if they may be placed under this heading, worth reading for amusement.”

Montaigne also blends the tales and anecdotes of his own age into his writing. In “On Drunkenness,” for example, he recounts the story of a chaste widow who discovers herself pregnant. After a long personal struggle to understand her pregnancy, she “brought herself to have it announced at the service in her church that if anyone would admit the deed, she promised to pardon him and if he saw fit, to marry him.” A farmhand in her employ confessed that he had “found her, one holiday when she had taken her wine very freely,” and was the father. “They are still alive and married to each other.”

Merci Beaucoup, Monsieur Montaigne

From this point on, when I reread pieces from books like Alice Thomas Ellis’s “Home Life One,” Pat Conroy’s “A Lowcountry Heart,” or Richard Mitchell’s “The Leaning Tower of Babel,” I will think of Michel de Montaigne standing behind them and all the other essayists I admire. We stand forever in his debt.

In his introductory remarks to his essays, Montaigne writes: “Thus, reader, I am myself the matter of my book; you would be unreasonable to spend your leisure on so frivolous and vain a subject.”

Ah, Monsieur Montaigne, how wrong you were.

Jeff Minick has four children and a growing platoon of grandchildren. For 20 years, he taught history, literature, and Latin to seminars of homeschooling students in Asheville, N.C. He is the author of two novels, “Amanda Bell” and “Dust On Their Wings,” and two works of non-fiction, “Learning As I Go” and “Movies Make The Man.” Today, he lives and writes in Front Royal, Va. See JeffMinick.com to follow his blog.

Be the first to comment