BROOKS COUNTY, Texas—Every week, deputy sheriff Don White heads out on remote ranchlands to search for the bodies of illegal immigrants.

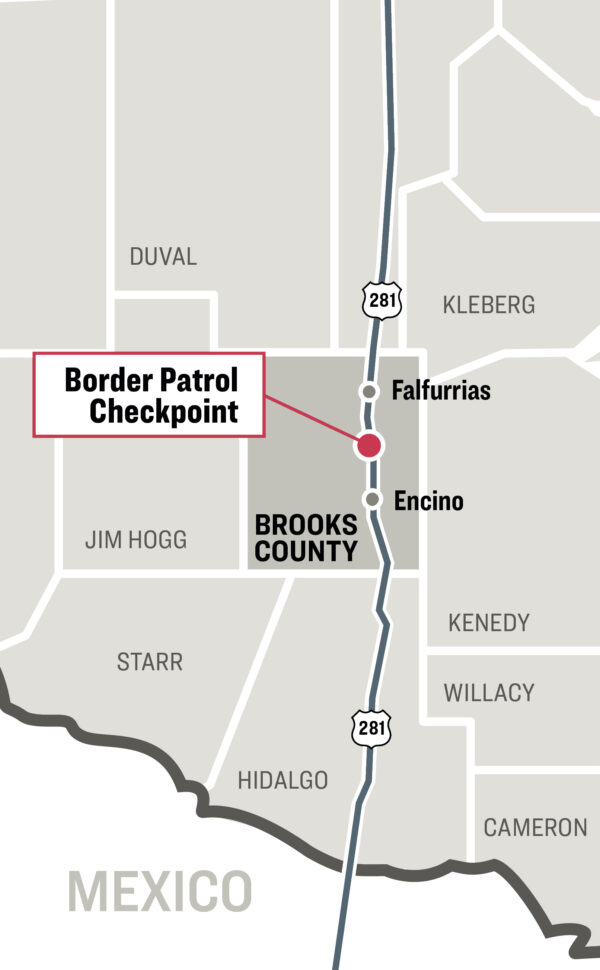

Brooks County is about 70 miles north of the U.S.–Mexico border, but it’s also where most of the bodies turn up.

The only way to skirt the Border Patrol checkpoint on U.S. Route 281 is to be dropped off south of it, walk north on private ranchland, sometimes for days, and then get picked up again—the next destination is usually Houston.

White said many illegal aliens who are trying to evade capture are dropped near the county line 12 miles south of the checkpoint.

So far in 2021, 33 bodies have been catalogued in the Brooks County Sheriff’s Office’s “death book.” The pages are filled with photos of bodies in varying stages of decomposition, including skeletons.

With the hottest months yet to come, this year is shaping up to be busy—on par with 2012, when 129 bodies were discovered. Last year, 34 bodies were found.

White, 68, volunteers his time and equipment to do the job; he aims to spend around 100 days per year searching for “the lost,” as he calls them.

Ranchers, local law enforcement, and Border Patrol agents also find bodies, but White says, “I search the areas no one else searches, to find the ones no one else is looking for.”

Over the past six years, White has gained permission from local ranchers to search their land. The county is 944 square miles and he reckons he now has access to about two-thirds of it. It might be a year or two before White covers the same ground, but he’ll check the more popular tracts—along pipelines and power lines—more frequently.

The busiest months are during summer, as most people die from a combination of dehydration and hyperthermia. Water is scarce, it’s not hard to get lost, and smugglers will leave illegal immigrants behind if they’re slow or injured.

The ones that don’t travel with a smuggler will usually be given a location that they’ll try to reach by using their phone to navigate.

But it’s not always the smuggler that leaves someone behind.

“My first search was for a kid that was left by his dad when [Border Patrol] was closing in. Dad called the Sheriff when he got to a safe place. Kid was never found,” White wrote on Facebook recently.

He’s sometimes given an area to search after a 911 call comes in, but the cell towers can’t always pinpoint a location. Other times, a family member will know the vague area the person was traveling in as well as when they were expected to be picked up.

Searching is slow work in scrubby terrain. White walks at just over a half-mile per hour, usually in a loose zig-zag pattern, looking for bones, tracks, trash, or any sign of human presence.

“I’m looking for, ‘Is a person’s gait normal?’ In other words, ‘Are they feeling OK?’ They’re not dragging their toes from injury or from being environmentally stressed,” he said. “Are their prints real deep, heavy heel strike, because they’re carrying a heavy backpack of drugs or something like that? So little things like that.”

White also has to continually check immediately ahead for rattlesnakes, and look still further up for wild hogs or anyone hiding from him.

“In years past, it wasn’t that much of an issue, they were just trying to hide from you,” he said. “Now, some of these people will try to take your resources because they know you’re going to have a vehicle somewhere.”

They’re also the ones who don’t want to be captured—more than 42,600 in April alone along the whole southern border.

“You have a whole group of people that, no matter what, they wouldn’t get an American status,” White said. “People already had convictions for murder, pedophilia, sexual assault, violence—all these serious crimes—and they’re not in the groups that are turning themselves in.”

Getting Lost

Once someone is lost, they can easily go further off-track and be harder to find. Then, once dehydration and hyperthermia are mixed in, it’s common for them to act irrationally.

White pointed out a spot where he found a man last year, next to a ranch road less than a mile from Highway 281. He was steps from a large blue barrel that a local humanitarian group periodically fills with water.

“He actually left his phone in the middle of the road, 30 yards away, across the fence. He’d taken off his shoes and T-shirt—put his shoes together and folded up his T-shirt. He died … trying to take his pants off. He was stressed. He was traveling by himself, because he still had his money, IDs, and everything else,” White said.

He said the man was from Tijuana, Mexico; he’d been deported three times, the last time being in 2015. It seems he was trying his luck crossing into Texas rather than into California.

Much of the time, White is looking for bones. It’s rare that he’ll find an intact skeleton, as animals have usually disarticulated a body and dragged parts around. Once he finds a bone, he’ll do his best to discern whether it’s human (some deer bones can look very human-like, he said), and then move in ever-widening circles to locate the rest of the body.

He carries various types of body bags in his Jeep and has a body rack bolted onto the rear for transporting. But if it’s small enough, or just a skeleton, it’ll ride in the back seat.

He can’t pinpoint why he has been drawn to body recovery for so many years, but it may have come from working homicide cases with the Bexar County criminal investigation division—”seeing people hurting and me being able to do something about it,” he said.

Perhaps that also prepared him for dealing with horrific scenes, such as finding a woman tied to a windmill, left to die after being raped. Or another young woman dead under a “rape tree,” with her underpants around her ankles. Rape trees are known locations where smugglers and others rape women and leave their undergarments on the tree as “trophies.”

As with other first responders and law enforcement, White keeps an emotional distance from what he encounters, and black humor is a way of coping.

“If you internalize everything, you’re a suicide statistic, basically,” he said.

His nonprofit, Remote Wildlands Search and Recovery, raises enough money to cover the gas costs of the volunteers who help him search one weekend per month.

Identifying the Bodies

Finding a body is only the first step in a long process.

A body can’t be released to the family until a death certificate has been issued, and a death certificate can’t be issued without the positive identification of the person.

White usually finds males aged between 19 to 40 years from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, or El Salvador.

Only about 30 percent of the bodies he finds have an ID.

“Most of the ones I find don’t have an ID because they’ve gone down and somebody else will take their identification,” he said.

“That’s heartless, because you’ve just stopped some family from getting their loved one back.”

If a body is fresh or recently deceased, it is usually sent to the medical examiner in Laredo, who will send a bone sample for DNA testing to Texas State University’s “body farm,” a facility that researches human body decomposition.

“The last recovery was last week. His clothing, his boots, the amount of time he’d been out there, his location, that all indicated who he was,” White said. “So he was transported to Texas State.”

It can take up to a year and a half to process the DNA for free, so, in some cases, the Argentinian group Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team will assist in paying for a quicker DNA test and help to locate the families.

“If there’s somebody we think we know who it is for sure, then they’ll step in and they’ll pay part of the fees or pay all of it to get it back in two months or sometimes three weeks. It just depends,” White said.

White has been recovering bodies for years—he spent 21 years as a recovery diver, before hanging up his oxygen tank last year to focus more fully on the ground in Brooks County.

It’s a thankless job in many ways, but “there’s a certain level of satisfaction knowing that some family will be feeling better due to my efforts,” he said.

“In the Hispanic culture, it’s very important that they have their loved one’s body,” he said. “They celebrate the Day of the Dead and if they don’t have the body back, then there’s no place they can go to, to worship, to say their thanks, to express their love for the individual. It’s just awful.

“So if I’m successful at what I do, then they’ll be able to settle their world a little.”

Be the first to comment