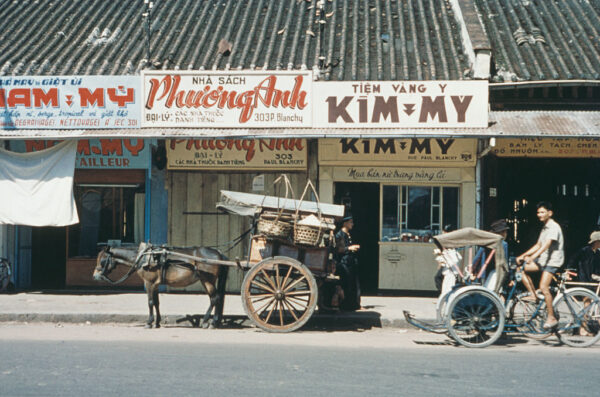

Over 46 years ago, on April 30, 1975, tanks of the Northern Vietnamese army rolled into Saigon (now known as Ho Chi Minh City), the capital of South Vietnam.

A soldier jumped from the tank and ran into the presidential palace to raise the Viet Cong flag on the balcony of the fourth floor.

The two-decades-long war between the capitalist South and communist North was over. Saigon had fallen to the communists.

Duc Nguyen was 10-years-old when this happened. In the space of several years, he would see the freedom-loving city he once embraced, transform and cause him to flee for his life.

“It is a world turning upside down,” Nguyen said.

“They would kick you out of the house if you have a house that they like,” he added. “They would say it is to serve the government’s purpose.”

The new government quickly made clear that their previous promises to be “in no rush to communise the South” were no longer valid. Newspapers were shut down.

Those who had ties with the previous government were identified as “bad elements” and refused access to university education. Former southern soldiers were pushed into labour camps, and religious institutions had to place portraits of North Vietnamese Communist leader Ho Chi Minh on the altars of their temples or churches.

“When you want to talk to someone on the street, you had to look over your shoulder because they might report you to the government, and the next thing you know is you are put in prison for saying something as silly as: ‘Today I’m so hungry, I don’t have enough food to eat,’” Nguyen said.

“They would force you to denounce your parents; they would force you to renounce religions. They would call that anti-revolutionary.”

After the regime implemented the socialist economy in Saigon, which allows the government to collectivise private property, the economy became devastated.

Inflation hit the peak rate of 453.5 percent in 1986.

So in 1978, Nguyen made the life-changing decision to flee to Australia, paying in gold ounces he secured himself one spot on a rickety fishing boat.

Nguyen was one of almost 800,000 Vietnamese people escaping Vietnam by boat to other countries and one of 110,000 people fleeing to Australia within 20 years since the communist takeover.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated about 200,000 to 400,000 of the refugees died at sea, calling it “an appalling human tragedy.”

“We didn’t have anything to eat… The boat had no cover, so it doesn’t matter if it’s sunny or raining; you just have to put up with it,” Nguyen said. “And then the pirates came. They raped the women. They didn’t kill anyone, though. It went on like this for about two weeks.”

After arriving in Australia, he met Trang Le, a Vietnamese girl who fled Vietnam in 1986. Like many boat people, she transited through Malaysia before landing in Australia.

Le still remembers the elation she felt when she saw a can of Coke stuck in the sand on the Malaysian shore.

“I hadn’t seen anything of this luxury for a very, very long time. And I just wanted to cry,” Le told The Epoch Times.

“It [the situation in Vietnam] was terrible to the point that I’d rather die in the ocean. I could be raped by pirates. My boat could be sunk. But I was willing to take that risk rather than living in a country under the communist regime,” she added.

Le and Nguyen married and had two children in Australia.

Le is now an accountant in Westpac, while Nguyen is an electrical engineer.

However, 40 years after escaping from his hometown, Nguyen is worried that the same ideologies that pushed his family into the sea are now rising on the land that he used to believe was a safe haven.

“The communists are very cunning,” Nguyen said. “They would say oh, look at these rich people, they are exploiting you. They talk about the things that actually work on paper only but don’t work in practice,”

He said communism uses the theory of struggles and egalitarianism and promises of a “communist heaven” to push people to revolt. He also expressed concerns about Australia’s trade with China and some recent Marxist movements, such as the Black Lives Matter protests.

“So the people in the West now are actually falling into the exact trap that was set out back then in China, Vietnam and Eastern European countries,” he said, “By the time they realised what it is about, the rope is already around their neck.”

Looking back on their life-changing journey to Australia, the couple felt overwhelmed.

“That trip has taught me that life is precious; you have traded freedom with your life,” Nguyen said, “We are extremely, extremely grateful for how we were received… in this country.”

Le agreed. She added: “It felt like you were reborn.”

Today, Vietnamese people is one of the largest ethnic groups in Australia, with about 300 thousand people claiming Vietnamese ancestry according to the 2016 census.

Be the first to comment