The Pentagon’s desperate plans to evacuate U.S. embassy personnel from Kabul as the Taliban sweep across Afghanistan are generating frequent comparisons to the fall of Saigon in 1975.

To Larry Chambers, however, that comparison is a little off.

“To be perfectly honest with you, what is happening now is worse than what happened in Vietnam,” Chambers said in an interview with Military Times, several days before the Taliban actually entered Kabul.

Chambers, now 92 and living in Sun City Center, Florida, has a unique perspective.

During the fall of Saigon, Chambers was skipper of the aircraft carrier Midway. Just months after taking command, he oversaw the evacuation of thousands of U.S. personnel and Vietnamese military and civilians during Operation Frequent Wind, which took place April 29 and 30, 1975.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/D5E33XG4ZZHWRJ3H2Y5H5WWE7A.jpg)

Helicopters from the Midway alone rescued more than 3,000 refugees, according to the USS Midway Museum.

For the Midway, the rescue operation began with the arrival by helicopter of South Vietnamese Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky, the former chief of the air force who had also served as prime minister, and Lt. Gen. Ngo Quang Truong. Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf, who served in Vietnam, called him “the most brilliant tactical commander I’d ever known.”

In the ensuing hours, wave after wave of helicopters arrived from the mainland, a 75 minute flight away, Chambers recalled. There were HH-53s loaded with 250 people, Hueys with 50, he said. Soon the deck was filled with frightened men, women and children fleeing death at the hands of the swarming enemy.

As the human misery unfolded, Chambers, the first Black aircraft carrier skipper, risked his career to help save those who helped the U.S. As Vietnamese air force Maj. Buang-Ly circled overhead with his family in a Cessna Bird Dog, dropping desperate notes on the deck, Chambers made a fateful and, as it turns out, historic decision.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/LAZ5JRTEVRBO5KVXCWQKODMYA4.jpg)

Despite being ordered to let Ly ditch into the sea, Chambers knew the man and his family would never survive. So he had his crew push millions of dollars worth of helicopters into the sea to make room for the small plane, which had no business flying over open water.

Chambers, who retired in 1984 as a rear admiral, said he knew he was risking a court-martial, but acted anyway.

“I have to live with my grandmother yelling in my ear ‘do the right thing,’” Chambers said, explaining why he made that decision to save Ly and his family. “Everyone has a conscience. You look at the options. There are no winners in these situations. You do the best you can, do the thing you know you can live with and figure you will pay the consequences for the act.”

The fact that other skippers were also pushing helicopters into the sea likely saved his career, said Chambers.

“As it turns out, because so many of the other vessels pushed one or two helicopters into the water, how do you go to court-martial?” he asked with a laugh. “But the others only had to push one or two over. This turkey pushed 25 or so helicopters off the deck.”

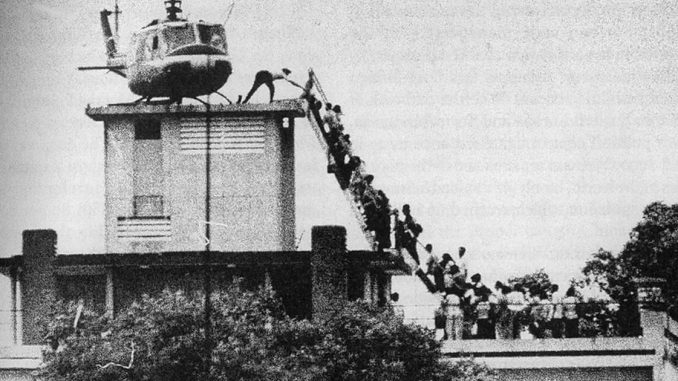

Chambers said he does not know the fate of the helicopter seen in that iconic image of a CIA officer pushing back people frantic to board it on a rooftop.

The fall of Saigon wasn’t the only rescue mission in which Chambers played a role.

Almost five years to the day later, on April 24, 1980, Chambers commanded the Coral Sea battle group, which was in the Arabian Sea waiting to provide air support if needed, during the failed attempt to rescue 52 Americans taken hostage in Tehran.

That mission, Operation Eagle Claw, ended in tragedy, as eight U.S. service members lost their lives during a fiery collision in the desert. President Jimmy Carter would only serve one term largely as a result of that debacle.

“Sometimes you are successful,” said Chambers. “Sometimes, you are not.”

On Thursday, Pentagon spokesman John Kirby announced that some 8,000 troops are being deployed to assist with the evacuation of personnel from the U.S. Embassy in Kabul as Taliban forces edge ever closer to the Afghan capital. That includes about 3,000 troops heading to Kabul. On Saturday, President Joe Biden ordered an additional 1,000 soldiers to Afghanistan to help secure that effort.

Speaking on CNN Sunday, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said: “This is not Saigon.” according to AP. However, he acknowledged the “hollowness” of the Afghan security forces.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/PTYG3YS5ZZGOFLAAMYGIK5YVQQ.jpg)

“I suppose you can draw a parallel” to the fall of Saigon, said Chambers.

“Of course it’s worse than Saigon,” he said Sunday.

“We tried to get out as many people who worked with us as we could,” he said Sunday. “Did we do a good job? Who knows? I do not know what [the Taliban is] going to do, but whaver it is not going to be pretty.”

“We made a promise to those folks that we would rescue them, and we didn’t,” Chambers said of the many left behind in what used to be South Vietnam. “In Afghanistan, we are abandoning the folks who supported us while we were there.”

One thing that makes the looming fall of Kabul so much worse than the fall of Saigon is that being closer to the ocean had its advantages, Chamber said.

“We had a huge amphibious force sitting off Saigon,” he said. “We don’t have a huge amphibious force sitting off Kabul.”

Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, is about 30 miles from the coast. Kabul, the capital of a landlocked nation, is about 800 miles from the Arabian Sea — way too far for an overloaded helicopter. Or a tiny airplane with a desperate family.

On Saturday, President Joe Biden authorized an additional 1,000 U.S. troops for deployment to Afghanistan according to AP, raising to roughly 5,000 the number of U.S. troops to ensure what Biden called an “orderly and safe drawdown” of American and allied personnel. In press conferences, Kirby, the Pentagon spokesman, has insisted the U.S. maintains the capability to evacuate thousands of U.S. personnel and Afghan Special Immigrant Visa applicants from Kabul via military transport.

But as the Taliban close in on Kabul, the risk to flights out of that country only increases. The lone runway at Hamid Karzai International Airport is flanked by mountains from which the Taliban can fire down.

Aside from transportation issues, the Taliban are a very different adversary than the North Vietnamese, Chambers said.

“Can you save them?” he asked of those Afghans who helped the U.S. and fear retribution from the Taliban if they are left behind. “You can save some, but you can’t save everyone who helped us. Remember all of those attacks by people willing to kill themselves? That is a different world over there as opposed to what we were facing in Vietnam.”

When asked about his grandmother’s voice yelling in his air about the right thing to do in this situation, Chambers acknowledged that he is not quite sure.

“That is a hard question,” he said. “I am totally unfamiliar with what is going on in Afghanistan. I don’t know what the right thing is, but suddenly pulling out probably isn’t it.”

Be the first to comment