Their artworks are icons of Italy and their names are among the most well-known in the art world: Donatello, Brunelleschi, Botticelli, Michelangelo. Eager viewers stop and snap photos of the instantly-recognizable paintings, sculptures, and buildings. Displayed in museums around the world, the immortal paintings invite a popular following. What remains obscured in the history books, however, is how many of these renowned objects and buildings came to be. The subject of patronage is one that is overlooked and misunderstood, and yet, without the patronage of families such as the Medici, the Renaissance as we know it today may not have happened. An overlooked, yet enjoyable, Italian series on Netflix dramatizes the rise of the Medici family in the fifteenth century, and viewers will glimpse prized commissions in several episodes: indeed, the architect Brunelleschi and the painter Botticelli are among the supporting characters.

The show hints at the concept of patronage without a more specific explanation. In simple terms, a patron is a person, family, or organization that financially supports artists. While some patrons commission a single artwork, others provide housing and stipends in exchange for the artist’s ongoing services. Until the Italian Renaissance, monarchs, nobles, and high-ranking clergy of the Catholic church (including the pope) were among the notable few with the financial means of patronizing the arts. Furthermore, the artwork that kings and cardinals commissioned served their own political aims and reinforced existing social hierarchies.

The Medici family amassed their fortune and created a dynasty through banking, a field which they helped modernize. The Medici Bank was founded in Florence, Italy in 1397, and for a century, it was the most formidable bank in Europe. Though the bank became defunct in 1499, the wealth that the Medici family generated ensured the power of the family for centuries more—in total, the Medici produced four popes, two queens, and countless aristocratic leaders.

Without coincidence, the ‘golden age’ of Medici banking paralleled a significant part of the Renaissance called the Quattrocento (which is the Italian word for ‘1400s.’) Cosimo de’ Medici secured his family’s political significance in Florence, and he also commissioned several notable pieces that are synonymous with the Florentine Renaissance today.

Among these commissions is Donatello’s David, a bronze sculpture which ushered in a new era in the medium.

Donatello’s David was completed sometime between 1420 and 1460; exact dates are unknown. Though exact records do not survive, art historians believe that Cosimo de’ Medici commissioned David to take pride of place in the the new Palazzo Medici. David simultaneously marked the prosperity of Florence and the revival of Western art: both feats thanks in part to the Medici family. David was the first free-standing bronze sculpture and first nude male sculpture since Antiquity (ancient Greece and Rome). Donatello fully realizes the mastery of his ancient predecessors with his perfect use of contrapposto, that is, the S-shaped way of casting David so that he appears naturalistic and human-like. His nudity emphasizes a rediscovery of the human form, which had not been valorized in art since Antiquity.

David’s facial expression is contemplative in the wake of his victory over Goliath, upon whose head he stands. Like many Renaissance artists that would follow him, Donatello studied ancient models, and the Medici family were among the earliest patrons to support this endeavor.

The architect Filippo Brunelleschi also enjoyed the Medici’s patronage, which resulted in a marvel that became the symbol of Florence itself: the dome of the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore (known more simply as the Florence Cathedral). Construction on the Cathedral began in 1296 and the original plans included a large dome on an octagonal base. There was only one problem: a dome of this size had not been built since Antiquity and the technology had been lost when the Roman Empire collapsed. With the financial and social support of the Medici, Brunelleschi studied the Pantheon, built in Rome in 125 CE .

However, the Pantheon had been constructed with concrete, and the recipe for the material had also been lost. Brunelleschi, then, engineered a double-shelled dome with a complex, innovative system of internal supports. He chose bricks for the exterior shell as it was lightweight and best suited to the structure he designed. Construction of the dome took 16 years, but its completion marked the beginning of the modern era in architecture and engineering. The dome, like the Medici family’s bank, attracted global reverence for the city of Florence.

While the dome of the Florence Cathedral attracts visitors from around the world, Sandro Botticelli’s masterpieces epitomize a pinnacle of the Western tradition of art. Lorenzo de’ Medici continued the legacy that his grandfather Cosimo initiated; indeed, Botticelli is among numerous artists that the younger Medici patriarch supported. Lorenzo de’ Medici also patronized the humanist and Neoplatonic philosophies which underpinned much of Botticelli’s works.

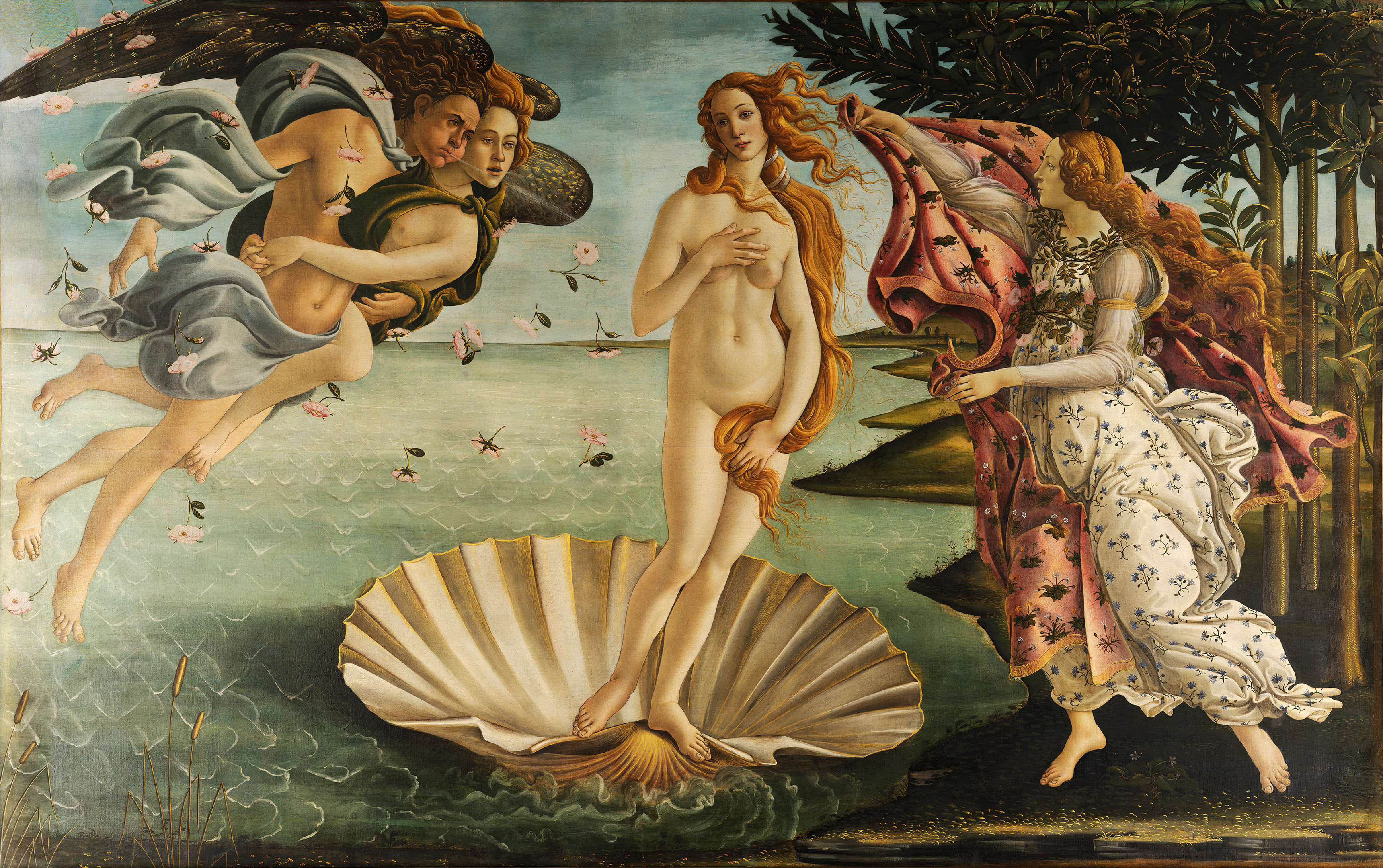

Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus and La Primavera are among the most well-known paintings in Western art. Venus, circa 1485, cannot be directly attributed to the Medici family, though they did own it at some point. The painting features the goddess Venus, emerging from the sea, newly-born as an adult. Notably, this depiction of Venus is the first non-biblical, fullscale female nude since Antiquity, further intwining the Italian Renaissance with Greek and Roman mythology. Zephyr, the god of wind, carries Aura, and a nymph drapes Venus: these, too, are all subjects adapted from mythology. The depiction is characteristic of Botticelli: Venus’s body is curved and some dimension is suggested, but she is also linear (being somewhat outlined) and holding an unrealistic pose.

Like The Birth of Venus, Botticelli’s La Primavera recreates pagan themes from ancient Greek and Roman sources. Once again, Venus is the central subject, though the scene and allegory are more complex. To the viewer’s left, the Three Graces dance in harmony. Importantly, the Three Graces—daughters of Zeus—are a common subject of Antiquity, and Botticelli has reintroduced them into Western art. Furthermore, he paints them from three different angles (front, side, back), which creates a spatially compelling composition. Other mythological figures, including Venus’s son Cupid, are depicted as well. The scene takes place in an orange grove, which is a direct reference to Medici symbolism and the Medici coat of arms. It is widely accepted that the Medici, most likely Lorenzo, commissioned the painting. It may allude to his Neoplatonic beliefs, and it certainly embraces and celebrates the Medici’s affinity for humanism.

Although mythological subjects were popular among the Medici and are a key feature of Renaissance art, biblical subjects also prevailed; David, described above, set a precedent for portraying Christian subjects with innovative methods and characteristics. Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment is perhaps the ultimate expression of the Medici family patronizing biblical art. Indeed, Pope Clement VII, who commissioned the piece, was the nephew of Lorenzo de’ Medici, noted above.

The Last Judgment, begun in 1536, covers an altar wall of the famed Sistine Chapel, where the artist had painted the ceiling two decades earlier. The importance of the altar wall cannot be underestimated: the College of Cardinals convene at this location to elect a new pope, a tradition which has continued for centuries. The subject matter, the Second Coming of Christ as described in the New Testament, had long been a traditional favorite among artists.

Michelangelo’s interpretation, however, brought a newfound psychological and visual intensity. To the viewer’s left, the blessed ascend to Heaven, and to the right, the damned are cast down to Hell. Christ scrutinizes the damned, pointing to his wounds. The Virgin Mary looks towards the blessed. Numerous saints surround Christ, and angels and demons participate in the frenzy. It is a powerful refutation of the Protestant Reformation, which was gaining momentum when Pope Clement VII commissioned this cautionary fresco.

Each of the artworks described above are masterpieces of the Florentine Renaissance, and advanced their respective media (painting, sculpture, architecture). The names and images alike are recognizable around the world. Without the patronage of the Medici family, however, many of these icons, along with countless others may not have come into existence. In viewing art, understanding how a piece came to be provides a deeper and often-overlooked meaning.

Dr. Kara Blakley is an independent art historian. She received her Ph.D. in Art History and Theory

from the University of Melbourne (Australia) and previously studied and taught in China and

Germany.

Be the first to comment