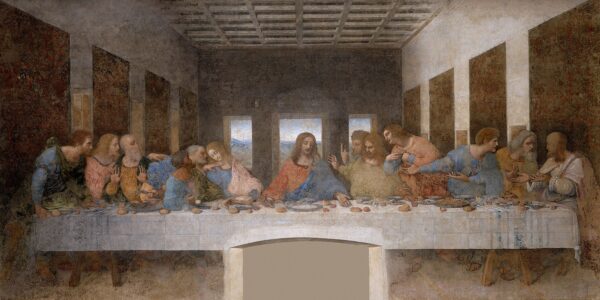

The Associated Press posted an article in 2007 about an Italian musician, Giovanni Pala, who believes he found a piece of musical composition hidden within Leonardo da Vinci’s famous painting “The Last Supper.”

Pala, a composer and computer technician, raises the possibility that da Vinci may have left behind a somber composition intended to accompany the famous scene. “It sounds like a requiem,” Pala claims, “emphasizing the passion of Christ.”

In his book, “La Musica Celata,” or “The Hidden Music,” Pala explains how he related different clues from religious symbols in the painting. Drawing five lines for a musical staff across the image, he was able to use these symbols, together with the positions of the hands of Christ and the disciples, to draw musical notes across the fresco. Further, Pala realized, the notes have to be read from right to left, according to da Vinci’s writing style, to make any sense.

The result, Pala claims, is a “hymn to God,” and sounds best when played on the pipe organ, an instrument commonly used during da Vinci’s time.

That particular painting, and da Vinci’s work in general, has been surrounded by mystique, with theory upon theory about hidden messages and meanings concealed within the work, proposed by even the most respected historians.

The fact that da Vinci himself was also an accomplished musician lent further weight to the idea—and after all, who doesn’t just love a good mystery? Even if Pala’s claims amount to no more than conjecture, it’s such a delightful conjecture. Pala himself said, “There’s always a risk of seeing something that is not there.”

But the article does remind us, once again, of the relationships and parallels between the arts. Pieces of classical music and painted masterpieces share more than a few structural similarities. So much so that in many ways we are either looking at or listening to the very same things.

There’s a dynamic at play that’s crucial to the foundations of all created art. And, although those dynamics are accomplished through different means by painters and musicians, without those dynamics or contrasts, there would neither be much to listen to nor look at.

For the fine artist, a flourish of bright red might be used in the same way a composer would use a piccolo or the first violin. Bright, high frequencies catch our attention and draw both the eye and the ear. In music, they’ll often delineate the main melody or theme, while the painter knows this will draw the eye and uses it accordingly, and often sparingly, to bring our attention to a particular motif or aspect of a painting.

It’s also true that a painter might surround a darker object with light, which will draw the eye to the darker object, but again, this use of relative contrast is the basis of the dynamic relationship for both disciplines: brights and darks, piccolos and basses, with all of the shades in between.

For the painter, soft pastels or warm ochers might suffice as calming or suggestive backgrounds, where in an orchestra, a section of cellos and violas might play a similar role. But the fine artist will choose those background colors in the same way a composer uses musical harmony to support the melody.

In the same way that a piece of music moves across a period of time, the arrangement of colors and shapes in a painting are said to create a sense of rhythm that leads the eye, in time, around the scene. While painters can be quite literal in terms of expressing emotion, by virtue of sad or smiling figures, musicians have the minor and major scales, quite literal tools, to indicate driving emotion.

It turns out that light and sound share quite a few similarities. They are both forms of energy that travel in waves. They each share the properties of wavelength and amplitude; however, light is electromagnetic and can travel through a vacuum, while sound needs a medium like air.

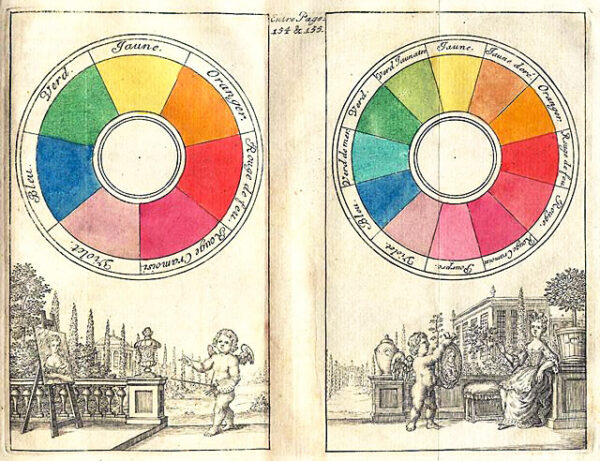

Isaac Newton actually had a color wheel that listed colors, exactly like a traditional artist’s color wheel, but alongside the colors were listed, according to their frequencies, musical notes.

According to Newton, there are mathematical relationships in the frequencies between music and light. The primary colors, for instance, adjusted for frequency, would sound out a major chord, and while there are just three primary colors, each chord of the major scale also has just three notes.

Further, the eight-note period of a musical scale (known as an octave), adjusted for frequency, would span the spectrum of colors on a color wheel, forming an octave of light.

And thus, dear reader, lovers of fine art and music can essentially see a symphony and listen to the beauty of a classical painting, without having to look for hidden musical notes in da Vinci’s “The Last Supper.” The entire painting is already the most sublime symphony for anyone who has the eyes to hear it.

Pete McGrain is a professional writer, director, and composer best known for the film “Ethos,” which stars Woody Harrelson. Currently living in Los Angeles, Pete hails from Dublin, Ireland, where he studied at Trinity College.

Be the first to comment