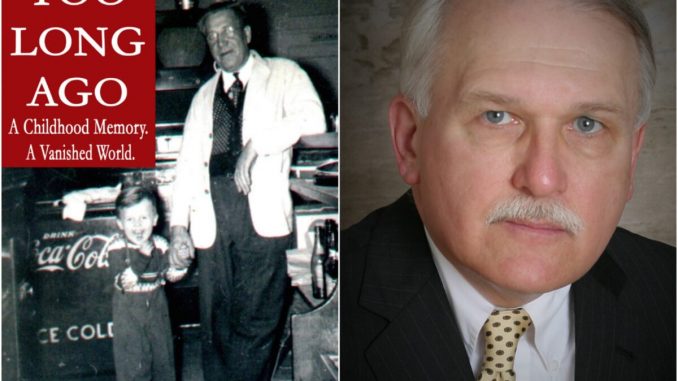

On the cover of “Too Long Ago,” there is a black-and-white photo of the happiest 4-year old boy you can imagine, holding his great-uncle’s hand at the latter’s bar in Amsterdam, New York. That boy is now the deservedly heralded presidential author and biographer, David Pietrusza.

Today, Pietrusza’s default facial expression is “business somber” (he appears more than occasionally on C-SPAN), and his memoir indeed explains the “stoicism” of many Polish Americans, an immigrant group whose odysseys and impressive successes in America haven’t gotten enough attention.

Yet Pietrusza has written an unsomber recollection of growing up in Amsterdam, New York, with affection, appreciation, and tongue-in-cheek observations of how his city and the United States operated in the 1950s and 1960s. “A vanished world,” he writes, right on the book cover.

Pietrusza admired noted raconteur Jean Shepherd, whom I got to know a bit during my early career years in New York television, while Shepherd was regaling listeners with tales of growing up in Indiana on WOR-AM five nights a week, without notes or scripts.

Shepherd would be proud of his devotee, as in Pietrusza’s analysis as to why his young self’s St. Stanislaus elementary school tuition was “a cool fifteen dollars a year” in 1950s Amsterdam: “Such a bargain was made possible by low overhead, and the school passed the savings on to us. Nuns, of course, were virtually slave labor. Or, at least, Slav labor.”

Such gems populate this fine recollection of a unique time and place.

This book only touches on the politics of the era, but does illustrate the value of cultural conservatism, from the properly reflexive anti-communism of Poles and their descendants to the central role of the Catholic church in pre-Vatican II upstate New York.

Pietrusza catalogs how general acceptance of Catholic values in Amsterdam created a generally kinder and gentler society than in the decades to follow. The drop-off in weekly Mass attendance and in vocations to the priesthood and the convent, he suggests, can be linked to the rapid rush to “reform” the Catholic church in the 1960s and ’70s.

Pietrusza introduces us to an array of memorable characters, many in his family, his neighborhood, and his school, and all of them real. He reports on Amsterdam being a “hard-drinking” city with many illegal gambling enthusiasts, but also a blue-collar, hard-working place as well.

Kirk Douglas and Benedict Arnold (the congressman, not the traitor) were sons of Amsterdam.

The carpet manufacturing mills were so central to the city’s economy, the minor league baseball team was named the “Amsterdam Rugmakers.” Runoff from the mills polluted tributaries of the Mohawk River to such an extent that locals could tell what color carpeting was made on a given day by the hues in the Chuctanunda Creek, and eventually the connecting great Mohawk.

Upstate New York is littered with cities that have declined as their primary industries found greener pastures in which to manufacture. Buffalo lost its steel mills; Rochester witnessed the collapse of Kodak and the departure of Gannett newspapers and Xerox’s corporate headquarters; Syracuse lost Carrier Corporation; and Amsterdam coughed up the carpet mills.

Correspondingly, the city’s population peaked at around 35,000 in 1930, with a steep decline of more than 50 percent, down to only some 17,000 residents today.

Among upstate cities, only Albany has a perpetual “manufacturer” and conveyor belt of every-increasing, high-paying jobs. Their primary “product” is immense and expanding state government, all at the expense of New York’s long-suffering taxpayers.

Pietrusza writes about family anguish as his father’s job in the mills disappears with his employer’s move out of New York. He provides a poignant travelogue about a family pilgrimage to Connecticut, where his father could visit the newly consolidated home of Bigelow-Sanford Carpet Mills, to see “where (his) job went.”

After a sequence of heavy lifting positions, the elder Pietrusza gets hired as a temporary U.S. Postal Service letter carrier, and eventually becomes permanent. David Pietrusza’s mother, also employed in manufacturing for years, eventually feels the gravitational appeal of government work herself, taking and passing the New York state civil service exam.

To get to her job in Albany each morning, Mrs. Pietrusza relied on a mix of carpools to traverse the 40-mile, one-way commute. But at least the family’s financial concerns had been put to rest.

One of the 1960s’ buzzwords was “urban renewal,” and Pietrusza explains how it came to Amsterdam, and with a vengeance. The downtown neighborhood was torn up in favor of an arterial highway that would speed motorists from the New York State Thruway across the Mohawk River.

The problem with this “renewal” was that the modern roadway bypassed restaurants and other establishments, as well as destroying homes and a church, accelerating the city’s decline. My family and I traverse this route each year, on our way to or from the Adirondacks, taking notice of St. Mary’s Hospital, which was built in part by my father-in-law’s work as a construction foreman.

Next time we’re in Amsterdam, thanks to Pietrusza’s entertaining memoir, we’ll be sure to get off that arterial, gassing up the car and sitting down at a local restaurant. We’ll be able to imagine that “vanished world” that Pietrusza has brought back to the mind’s eyes of his readers.

“Too Long Ago:

David Pietrusza

Church & Reid Books, 2021

319 pages

Herbert W. Stupp is the editor of GipperTen.com. He was a New York City commissioner from 1994 to 2002.

Be the first to comment