President Donald Trump on Tuesday commuted the sentences of two eastern Oregon ranchers serving time in federal prison for setting fire to public land in a case that inflamed their supporters and gave rise to the armed takeover of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge.

The decision will free Dwight Hammond Jr., 76, and son Steven Hammond, 49, convicted in 2012 of arson on Harney County land where they had grazing rights for their cattle. They were ordered back to prison in early 2016 to serve out five-year sentences.

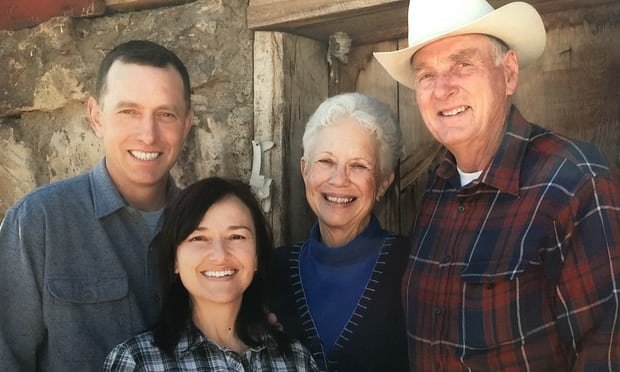

“The Hammonds are devoted family men, respected contributors to their local community and have widespread support from their neighbors, local law enforcement and farmers and ranchers across the West,” the White House said in a prepared statement. “Justice is overdue for Dwight and Steven Hammond, both of whom are entirely deserving of these Grants of Executive Clemency.”

Susie Hammond, Dwight’s wife and Steven’s mother, said she was sound asleep Tuesday morning and awakened by a call from U.S. Rep. Greg Walden. “He said it’s a done deal, the papers were signed,” she recalled. “We’ve been waiting a long time. I think it’s wonderful.”

Though Susie Hammond believed her husband and son had a strong case for clemency, she was reluctant to get her hopes up.

“I’ve just been sitting here, on the phone since,” she said. “I still can’t believe it. I won’t believe it until I see them.”

Trump’s move marks yet another big victory for backers of the Hammonds, including Ammon Bundy and his followers who repeatedly cited the case as the trigger for the 41-day occupation of the wildlife refuge that abutted the Hammond family ranch. Bundy viewed the case as an example of the federal government run amok. A jury acquitted him and other key takeover figures of all federal charges.

Widget not in any sidebars

Both Hammonds were convicted of setting a fire in 2001, and the son was convicted of setting a second fire in 2006. A federal judge initially sentenced the father to three months in prison and the son to one year after they successfully argued that the five-year mandatory minimum was unconstitutional.

They served the time and were out of prison when prosecutors challenged the shorter terms before the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and won. Another federal judge in 2015 sent the ranchers back to complete the full sentences.

According to the Trump administration, federal prosecutors who challenged the Hammonds’ original sentence filed “an overzealous appeal” that resulted in full five-year sentences.

“This was unjust,” the White House said in its statement.

As of this month, Dwight Hammond has served two years and eight months in prison and 31 months of supervised release. His son has served three years and three months in prison and two years of supervised release.

Susie Hammond, Dwight’s wife and mother to Steven, several weeks earlier heard that Trump was considering a pardon. At that time, she said she had a “sense that things are moving forward and I have faith in our president. If anyone is going to help them, he’d be the one.”

The federal criminal case that made Steven and Dwight Hammond Jr. martyrs to an angry cadre of protesters was built around controversial mandatory minimum sentences. Federal prosecutors refused to budge off their demand the Hammonds serve five years.

In clemency petitions, lawyers for the Hammonds cited the ranchers’ longtime service to their Harney County community, the severity of their punishment, the trial judge’s support and their family situation.

“Unlike some cases where clemency may outrage the community, clemency for the Hammonds would be embraced by the Oregon community, both rural and urban,” wrote Larry Matasar, Steven Hammond’s attorney.

The lengthy sentences, plus the U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s refusal in 2014 to renew a grazing permit for the Hammond ranch, have crippled the operation, the family has said. The Hammonds have appealed the federal agency’s denial.

“If the Hammonds are unable to return to the ranch in the near future, the legacy and livelihood Dwight and Steven Hammond have been building for their family could truly be lost,” Matasar wrote in his petition. “A clemency would not only serve as a balm to the community’s angst about these sentences, but very practically, give the Hammonds a real chance to keep their ranch afloat.”

Dwight Hammond set a prescribed burn on about 300 acres of his own land that then traveled onto Bureau of Land Management property and burned an additional 139 acres, his lawyer wrote. The elder Hammond said he was trying to fend off invasive species.

Prosecutors argued the fire also was to cover up illegal deer poaching and got out of control, placing firefighters who had to be airlifted out of the area in grave danger.

The federal pursuit of the Hammonds followed years of permit violations and unauthorized fires, and they never accepted responsibility, said Oregon’s former U.S. Attorney Amanda Marshall. Her office appealed the lighter sentences because she said the trial judge didn’t have discretion to depart from a mandatory minimum sentence. The Hammonds could have faced less than a year in prison under a plea offer they declined, she said.

The Hammonds’ lawyers, including attorney Kendra Matthews for the elder Hammond, pointed out in their clemency petitions that the father and son faced other sanctions. They paid $400,000 in 2015 to settle a civil suit brought by the government and are having a hard time sustaining the cattle operation because of the grazing permit denial.

They cited the opinion of the trial judge, U.S. District Judge Michael Hogan, who found the five-year sentences “grossly disproportionate to the severity of the offenses here” and noted that the fires didn’t endanger any people or property.

Harney County Sheriff Dave Ward, U.S. Rep. Greg Walden, Malheur County Sheriff Brian Wolfe as well as leaders of the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association and Oregon Farm Bureau wrote letters in support of the Hammonds’ clemency petitions.

Ward, who was the face of law enforcement during the 2016 occupation of the wildlife refuge in his county, wrote that he personally felt the initial sentences and the financial penalties “covered the debt owed to society.”

“This case was thrust into the national spotlight when, for lack of a better term, anti-government extremists exploited the Hammond family and began attempting to use their unfortunate circumstance to gain support for their own agendas,” Ward wrote.

He noted that Dwight and Steven Hammond rejected pressure they faced from Ammon Bundy and others to defy federal orders and instead turned themselves in to prison.

“It is my humble opinion that justice would be better served if these gentlemen were afforded the opportunity to return home,” Ward wrote. “For Dwight to spend his remaining years with his wife. For Steven to return to his family … and to set an example that along with being a nation of laws, we are a nation of compassion and forgiveness.”

Other letters of support described good deeds done for their neighbors, children and grandchildren’s schools, the county’s 4H and FFA clubs and many others in need. They spoke of Dwight Hammond’s sincerity, decency, his humility and the respect for him in Harney County — a man who dressed up as Santa Claus for schoolkids and what one friend described as “a real life John Wayne.”

Widget not in any sidebars

Dwight Hammond’s wife, who is ailing, lives alone in Burns. Steven Hammond is married with three children.

“I am seeking commutation of my sentence so that I can return home to take care of my wife,” Dwight Hammond wrote. “I live in fear that one of us will pass before we are reunited.”

Trump’s action follows a flurry of pardons, including for Dinesh D’Souza, a conservative author convicted of illegal campaign contributions; I. Lewis Libby Jr., a former aide to Vice President Dick Cheney; former Arizona Sheriff Joe Arpaio; and Alice Johnson, 63, serving life for her role in a cocaine distribution ring.

— mbernstein@oregonian.com

503-221-8212

@maxoregonian

Be the first to comment